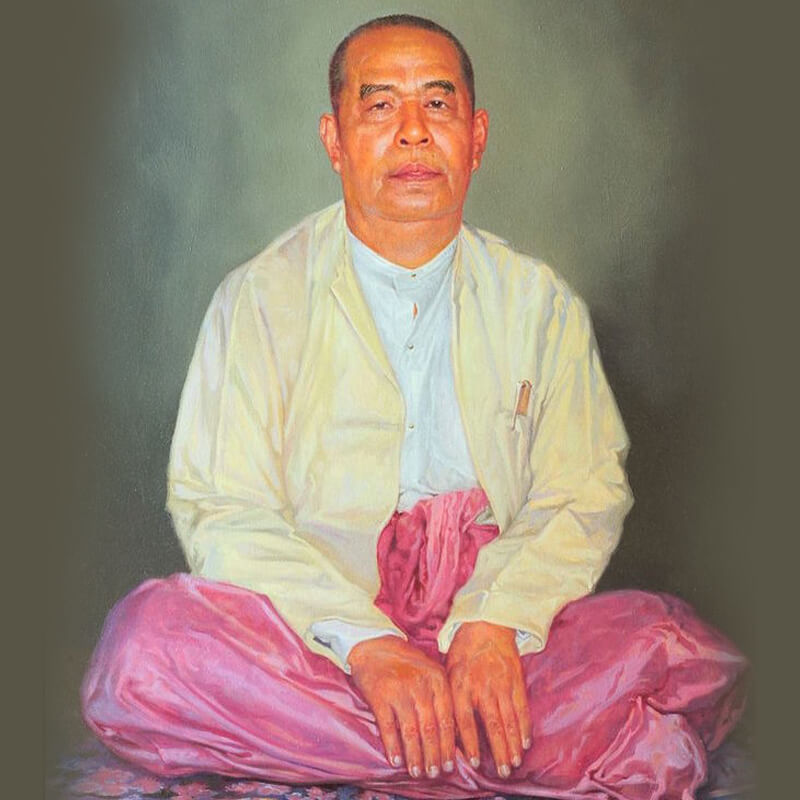

My teacher, My Benefactor

-By Mr. S. N. Goenka

It was eighteen years ago, my physicians in Burma advised me to get myself treated in foreign countries; otherwise there was a danger of my becoming a morphine addict. I was suffering from a severe type of migraine since my childhood, the intensity and frequency of which had increased with the years. Even the best doctor in Burma had no treatment for it except that he administered a morphine injection whenever I suffered from an attack which came about every fortnight. This was certainly not a treatment. That is why they warned me that there was a danger of my starting to crave for morphine; not because of the headaches, but because of my gradual addiction to it.

On their advice, I made a trip round the world and for months together was under the treatment of some of the best doctors in Switzerland, Germany, England, the United States and Japan. But it was all in vain. It proved a sheer waste of time, money and energy. I returned no better.

At this stage, my good friend (Kalyan Mitra) U Chan Htoon, who later became a judge on the Supreme Court of the Union of Burma and President of the World Fellowship of Buddhists, guided me to Sayagyi U Ba Khin. I shall always remain grateful to him and shall keep on sharing with him all the merits that I accumulate while treading this Noble Path.

My first meeting with this saintly person, U Ba Khin, had a great impact on me. I felt a great attraction towards him and the peace which emanated from his entire being. I straight away promised him that I would be attending one of

his ten-day intensive Vipassana meditation courses in the near future. In spite of this promise, I kept on wavering and hesitating for the next six months, partly because of my scepticism about the efficacy of meditation in curing my migraine which the best available medicine in the world could not do, and partly because of my own misgivings about Buddhism, having been born and brought up in a staunch, orthodox and conservative Sanatani Hindu family. I had a wrong notion that Buddhism was a pure nivriti-marg, a path of renunciation and had no real hope for those who were not prepared to renounce the world. And I was certainly not prepared to do so at the prime of my youth.

The second misgiving was my deep attachment to Swadharma (one’s own religion) and strong aversion to Paradharma (other religions) without realizing what was Swadharma and what was Paradharma. I kept on hesitating with these words of Bhagavadgita ringing in my ears:Swadbarme Nidhanam shreyah paradharmo bhayavabah”. (“Better die in one’s own Dharma because to follow another’s Dharma is perilous.”)

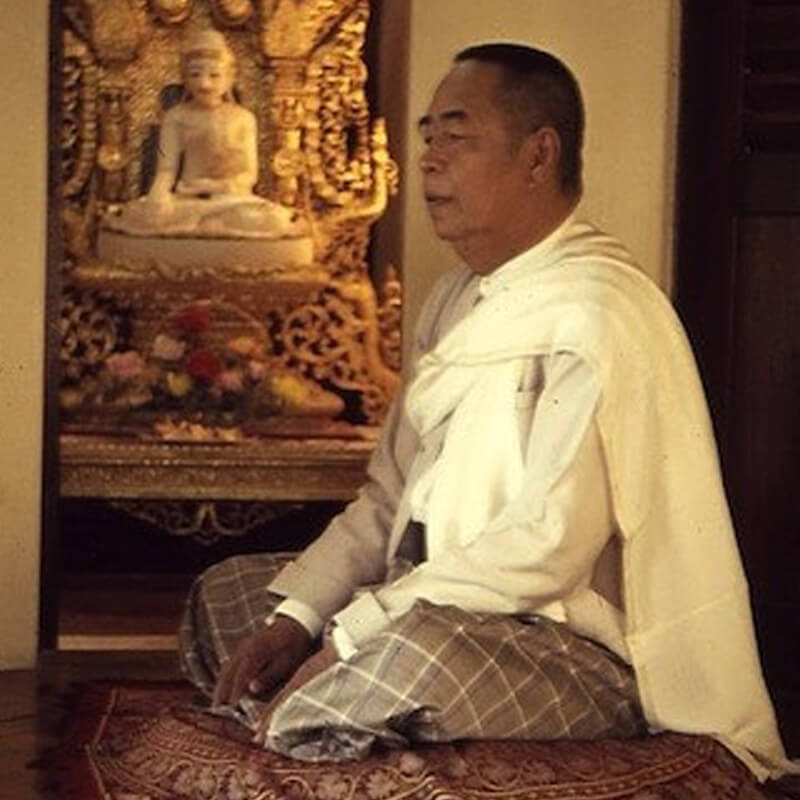

In spite of these hesitations, there was something deep within me which kept on pushing me towards that great saint; towards the Vipassana Center at Inyamyaing, the Island of Peace, and towards that Noble Path with which I must have had past acquaintance although I was unaware of it then. Hence, after the monsoon was over, when the meditation courses were resumed at the Center, I participated for ten days.

These were the most illuminating days of my life. The migraine had proved a blessing in disguise. A new Goenka was born. A second birth was experienced in coming out of the shell of ignorance. It was a major turning point in my life. Now I was on the straight path of Dhamma without any blind alleys from which one has to retreat one’s steps. I was on the royal road to real peace and happiness, to liberation and emancipation from all sufferings and miseries.

All the doubts and misgivings were gone. The physical suffering of migraine was so trivial compared to the huge mass of invisible suffering in which I was involved. Hence a relief from migraine was a mere by-product. The self-introspection by Vipassana had shown me that my whole being was nothing but a mass of knots and Gordian knots of tensions, intrigues, malice, hatred, jealousy, ill-will, etc. Now I realized my real suffering. Now I realized the deep rooted real causes of my suffering. And here I was with a remedy that could totally eradicate these causes, resulting in the complete cure of the suffering itself. Here I was with a wonderful detergent which could clean all the stains on my dirty psychic linen. Here I was with a hithero unknown simple technique which was capable of untying all those Gordian knots which I had kept on tying up ignorantly in the past, resulting all the time in tension and suffering.

Walking on this path, using this detergent, taking this medicine, practicing this simple technique of Vipassana, I started enjoying the beneficial results, here and now, in this very life. The Sanditthiko and Akaliko qualities of Dhamma started manifesting themselves and they were really fascinating to me, for like my teacher, I too had been a practical man all my life, giving all the importance to the present.

Now I was established on the path from which there is no looking back but a constant march ahead. Not only my migraine was totally cured, but all my misgivings about the Dhamma were also gone.

I fully understood that a monk’s renounced life was certainly preferable to achieve the goal with the least hindrance, but the householders’ life was not an insurmountable barrier to the achievement. Millions upon millions of householders in the past and present have benefited from this Eightfold Noble Path which is equally good for the monks as well as the householders, which is equally beneficial to young and old, man and woman: verily, to all human beings belonging to any caste, class, community, country, profession or language group. There are no narrow sectarian limitations on this path. It is universal. It is for all human beings for all times and all places. Because all human beings are victims of the same illness manifesting itself in different ways and forms, the remedy is therefore equally applicable to all the patients. So I kept on benefiting from the Path even as a householder, discharging my duties more successfully and efficiently. Now I fully realized what was real Swadharma of Sila, Samadhi, and Pañña, and getting away from the paradharma of lobha, dosa, and moha.

In a few years time a big change started manifesting in my life, in my outlook, in my dealings with different situations. I started realizing that the path does not teach us to run away from problems. It is not ostrich-like escapism. We have to face the hard realities of the life and it gives us the necessary strength to face them with peace and equanimity of mind. It gives us an Art of Living – living harmoniously with our own selves and with all those with whom we come in contact in the social field. The gradual purification by this technique keeps on making the mind calm, clear, and steady. It takes away the confusion and cloudiness, the tensions and turmoils, the waverings and doubts of the mind, as a result of which its capacity to work increases many-fold. We start working more effectively and efficiently.

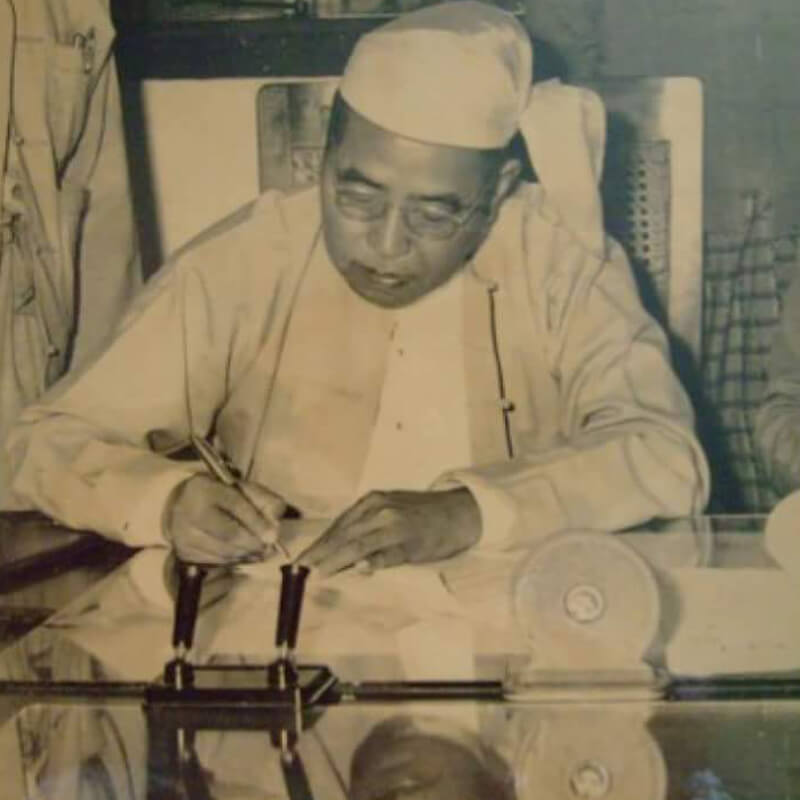

I started noticing it in my own life. This came as a great boon to me in my business life because my capacity to work efficiently had increased tremendously. Sayagyi U Ba Khin was himself a brilliant example of this achievement. His capabilities and integrity were exemplary. It was for this reason that he was asked to hold more than one top executive post simultaneously. At one time he was holding four such posts concurrently and still gave record results. It was for this reason he was made to keep on serving the various successive governments for twelve years after the age of retirement at fifty-five.

His life was a source of inspiration to his students including myself. He held such important executive posts where he could have easily amassed millions clandestinely in foreign banks. But that was not the way of Dhamma.

That was not the way of Dhamma Vihari U Ba Khin. He felt fully satisfied to have left only a small cottage type house for his son and daughters as the only saving of his honest earnings.

Neither the inducement of money from dishonest traders, nor the threatening pressures from the political bosses could deter him from taking right decisions. There were many occasions in his life when he displeased the business magnates of the country, his colleagues in the civil service and so also his political bosses, the ministers in the cabinet because he would not comply with their wishes which he found illegal and immoral. Neither fear nor favour could shake him from taking right decisions and actions in his mundane duties. Similarly, no illusion or delusion, no hair-splitting controversies of the theoreticians, nor the attraction of fame or aversion to defame could deter him from his practice and teachings of the Dhamma in its pristine purity.

Besides being an ideal government executive with outstanding ability and integrity, he was a human teacher of the Noble Path. He conducted his classes with immeasurable love and compassion for the students in spite of his steellike rigidity for strict discipline. At the International Meditation Center, he gave equal compassionate attention to the ex-president of the country and a peon, to the judge of the Supreme Court and a criminal.

Such was U Ba Khin, a jewel amongst men. Such was my noble teacher who taught me the art of a sane life. Such was my benefactor who made me reap the rich harvest of Dhamma Ratana which has proved much more valuable to me than all the material wealth that I had accumulated in my business life. Such was my compassionate physician who cured not only the illness of my head nerves, but also the illness of my psyche which used to keep me tense and tormented my whole life.

It was my great puñña-parami indeed, that I was born and brought up in Burma, the land of living Dhamma; that I came in contact with Sayagyi U Ba Khin, the saintly exponent of the Noble Path; that I could avail myself of his compassionate guidance and proximity, to practice the Saddhamma continuously for fourteen years; that now I find myself in an unexpected opportunity wherein I can gratefully serve my teacher in fulfilling his lifelong cherished desire to spread the applied Dhamma to the suffering humanity so that more and more people at large can get Shanti-sukha, the peace and harmony that they badly need.

While in Burma I had the privilege of sitting at his pious feet and translating his words into Hindi language for his Indian students for about ten years. It was indeed a sacred opportunity for me to have remained so near to him and near to his infinite Metta waves. Then it so happened that two and a half years ago I received a message from my mother in Bombay that she was ill and when her condition deteriorated she started calling me to come to see her.

The Revolutionary Government of Burma was kind enough to grant me the necessary passport valid for a visit and stay in India for a period of five years. Hence, in June 1969, I came to Bombay, and with the blessings of Sayagyi, I conducted the first course of Vipassana meditation for the benefit of my mother, wherein thirteen others participated, some known, and others unknown, to me. At the conclusion of the course, my mother was greatly relieved of her illness and other participants were also immensely benefited. On repeated requests from these participants and to serve further my old ailing mother, I conducted a few more courses with the blessings of Sayagyi and then the ball started rolling. Receiving requests from different parts of India, I kept on moving and conducting course after course from place to place, where not only local residents but people from different parts of the world started participating All these courses were conducted under the personal guidance and blessing of my teacher. Even after his passing away one year ago, observing the continued success of these courses, I get more and more convinced that it is his Metta force which is giving me all the inspiration and strength to serve so many people from different countries. Obviously the force of Dhamma is immeasurable.

May glory be to the Dhamma. May glory be to my country which preserved Dhamma in its pristine purity for over two millennium. May glory be to my teacher whose name will remain shining in the galaxy of all the luminaries of the Kammaμμh±na tradition right from that great teacher of teachers, the Tathagata Buddha, up to those of the present age.

May the sunshine of Dhamma illuminate the entire world and dispel all the darkness of ignorance. May all beings be benefitted by Dhamma. May they be peaceful. May they be happy.

(Courtesy: The Maha Bodhi journal)

Modern Interpretation of the Teaching of the Buddha

—By U Ko Lay, former Vice Chancellor of Mandalay University

His understanding of Dhamma, as taught by the Buddha, was profound and penetrating; his approach to it modern and scientific. His was not mere conventional acceptance of the teaching of the Buddha; his was a whole-hearted embrace of Dhamma with firm conviction and faith as a result of personal realisation through actual practice.

He learned Vipassana meditation at the feet of Saya Thetgyi. When he reached a certain stage of proficiency, Saya Thetgyi felt certain that Guruji U Ba Khin was destined to play the role of the torch-bearer after he had passed away.

But it was only after he had met and paid homage to Webu Sayadaw, believed by many to be an arahant, in 1941 that he finally decided to help people find the Path laid down by the Buddha.

He felt the need of a course of instructions particularly for householders, rather than strictly for bhikkhus (monks) and recluses who had given up worldly life. A discipline for bhikkhus could not ideally be suitable for laymen. The Vipassana Research Association, initiated by Sayagyi while he was the Accountant General of Burma, undertook research and experiments in Vipassana meditation. Results and findings from these studies carried out in a special shrine room at the A.G.'s office enabled Sayagyi to present the Buddha's Dhamma to laymen in a systematic, scientific manner, thus appealing to the modern mind. His regimen of Vipassana exercises encompasses completely the three requisites laid down by the Buddha (namely sīla, samādhi and paññā, but is so streamlined and disciplined that satisfactory results could be expected within a short period of endeavor.

Foreign intellectuals and organizations first became acquainted with Sayagyi when he gave a series of lectures to a religious study group composed of members of a special technical and economic mission from America, in 1952. The lectures, rendered in booklet form, soon found their way to various Burmese embassies abroad and Buddhist organisations the world over.

Sayagyi made a few more expositions of the life and teachings of the Buddha, but mere interpretation of the Dhamma had never been his main object. He applied himself solely to the task of helping sincere workers to experience a state of purity of mind and realise the truth of suffering resulting in "the peace within" through practicing Vipassana meditation. He achieved astounding results with the presentation he developed to explain the technique. To his last breath Guruji remained a preceptor rather than a preacher of Vipassana meditation.

Human Qualities of the Teacher

—By Mrs. Vimala Goenka, senior assistant teacher to S. N. Goenka

I once considered Sayagyi U Ba Khin an old, dry and uninteresting person who taught something which was fit only for aged people who had little interest and activity in the things the outside world offered. I regarded him with awe and fear, for I had heard much about his outbursts of anger. I visited him at the centre with the elders of my family very seldom, and only when I had to.

All these feelings evaporated, one by one, when I stayed with him for ten days and learned meditation under his guidance.

I found Sayagyi to be a very affectionate person. He was like a father to me. I could freely discuss with him any problem that faced me, and be sure not only of a sympathetic ear but also of good advice. All his anger, which was talked about, was only surface-deep; the core was filled with unbounded love. It was as though a hard crust had formed upon a liquid material. The hard crust was necessary-rather, very important for the work he was doing.

It was this hardness, which enabled him to maintain strict discipline at the centre. Sometimes people took undue advantage of his loving nature and neglected the purpose for which they were there. They would walk around the place and talk with other students, thus wasting not only their own time, but disturbing others as well. Sayagyi's hard nature was required to set them on the right track. Even when he got angry, it was loving anger. He wanted his students to learn as much as possible in the short time available. He felt such negligent students were wasting a precious opportunity, which might never come again, an opportunity of which every second was so precious.

The beauty and peace he created at the centre will always linger in my heart. He taught a rare thing, which is of great value to old, and young alike. He was a great teacher and a very affectionate man indeed.

A Living Example of Dhamma

- By John Coleman

To say that U Ba Khin was an impressive person would be an unforgivable understatement. He was much more. He was a living example of the fruits of the Dhamma who showed that the teachings of Buddhism had something very important to offer, today perhaps more than ever before. Here was a man in the evening of his life carrying a heavy burden of government responsibilities and enjoying an extraordinarily active life, who at the same time was engaged in a mission whose sole aim was to help others find the creative joy he exemplified.

He was a powerhouse of dynamic energy, sleeping only a few hours each day and dividing his time between government duties and his work at the meditation centre. In the short time I spent with him on that first and subsequent occasions, I came to know U Ba Khin as a gentle, quietly-spoken and humorous teacher, a profound thinker, a lover of beauty. I found that to him beauty, compassion, spiritual peace, truth, morality and love were not just words, nor were they an end in themselves. They were a way of life, part of his very existence.

(Courtesy: International Vipassana Newsletter, Winter 1981)

Qualities of the Man

-Dr. Om Prakash, former consulting physician, United Nations Organisation, Burma;

senior assistant to S. N. Goenka

His was a fine personality: majestic, sober, noble and impressive. He always bore a faint smile and the look of a calm, satisfied mind. When with him, you felt as if he cared for you and loved you more than anybody else. His attention, love, mettā was the same for all, big or small, rich or poor.

He never asserted anything, never forced any idea on you. He followed what he preached or taught and left it to you to think over and accept his view in part or in full as you wished.

He had a great aesthetic and artistic sense, loved flowers very much, and took special care about getting rare varieties. He knew all his plants well and would talk about them at length with the centre's visitors.

He had a good sense of humour. He was fond of making little jokes, and laughing, laughing very loudly. Just as he would shout loudly, he would laugh loudly!

He kept himself well informed about world politics and the modern advances in science and technology, and was a regular listener to radio and a reader of foreign periodicals. He was especially fond of Life and Time magazines.

He bore disease and illness bravely and well, and was a very intelligent and co-operative patient. He never took a pessimistic view of life; he was always optimistic and took a hopeful view. He took suffering and disease as a result of past karma and said it is the lot of one born into the world. Even his last illness, which came and took him away from us suddenly, he treated very lightly.

He was a very pious and great soul; pure of mind and body, and loveable to everyone.

An Academic Assessment

—By Winston L. King, Prof. of Religion, Vanderbilt University

The center [I.M.C.] is actually the projection of the personal life and faith of its founder, U Ba Khin, who is its director and Gurugyi also. He is now a vigorous man, just over sixty, who in addition to the center work—where he spends all of his out-of-office hours during the courses—holds two major government responsibilities.

By any standards, U Ba Khin is a remarkable man. A man of limited education and orphaned at an early age, yet he worked his way up to the Accountant Generalship. He is the father of a family of eight. As a person, he is a fascinating combination of worldly wisdom and ingenuousness, inner quiet and outward good humor, efficiency and gentleness, relaxedness and full self-control. The sacred and the comic are not mutually exclusive in his version of Buddhism; and hearing him relate the canonical Buddha stories with contemporary asides and frequent salvoes of throaty “heh, heh, heh’s,” is a memorable experience.

…Because of his ability to achieve both detachment and one-pointed attention, he believes that his intuitional and productive powers are so increased that he functions far more effectively as a government servant than most men. Whether he is a kind of genius who makes his “system” work or whether he represents an important new type in Burmese Buddhism—the lay teacher who combines meditation and active work in a successful synthesis—is not yet clear in my mind.

—excerpted from A Thousand Lives Away: Buddhism

in Contemporary Burma, written ca. 1960

My Teacher’s Boundless Mettā

-By Mr. S. N. Goenka

Sayagyi was the epitome of compassion and loving-kindness. Although deeply engrossed in official duties, he was full of enthusiasm for giving Dhamma service to the maximum number of people. He taught Dhamma to any person who approached him, even if it caused him much inconvenience. Sometimes he would hold a course for even one or two students, and would exert as much effort for them as for a large number. His mind remained suffused in love for every student. They seemed like sons and daughters to him. Only three days before he passed away, he completed a course. And until the day before his demise, he was still teaching Dhamma.

He had immense love and compassion for all creatures. All Creatures at his centre, even snakes and scorpions, were affected by his boundless mettā (loving-kindness). Every particle of the centre radiated with his love. He tended the trees and plants there with great compassion. It was because of his strong mettā that the fruits growing in that sacred piece of land came to have an exceptional sweetness and flavor. The flowers also had a distinctive hue and fragrance.

One year something unusual happened in Burma. A situation bordering on famine developed. This was a shock for a country like Burma, which had always produced an abundant harvest. Food production was diminished and the government had to introduce rice rationing. The people were deeply affected by this. At this time Sayagyi’s compassion for his afflicted countrymen knew no bounds. Not only from his lips, but from every pore of his body seemed to resound the sentiment: "May the people be prosperous, may the ruler be virtuous!"

Sometime later a famine also occurred in India, continuing for two years. Sayagyi’s compassion was enlivened once again. In one corner of his centre he had arranged to have erected a model of the lofty peaks of the Himalayas. He was very fond of this reminder. He would meditate beside it every day, sending his goodwill to India with the wishes: "I cannot recall how many times I was born in India and remained in that snow-clad region for so long, developing my meditation. Today the people of that country are in distress. May peace and tranquility come to them. May all abide in Dhamma!"

Most Venerable Teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin

-By Mr. S. N. Goenka

I was born and brought up in an orthodox Hindu family. Since childhood, the ideology expressed/represented by the Gita Press, Gorakhpur left deep impression on my psyche. Devotion to God was the very basis of my life.

My Babaji (grandfather Shri Basesarlalji) used to visit the majestic Sānju Pagoda in Mandalay almost daily. My brother Babulal and I were very small at that time. On Sundays, the school being closed, we also used to accompany him. There is a very big and attractive statue of Lord Buddha in the Pagoda. Some people used to sit silently before that. Our Babaji would also sit with them. We had two reasons to accompany him there – one, children were allowed to travel free in electric trams those days and secondly, it afforded us a good opportunity to spend our Sunday holiday. We would spend an hour or half there in playing and at times I would sit quietly beside Babaji for 5 to 7 minutes. I was very fond of sitting there in silence. I do not know what my grandfather did there for such a long time. There were big temples of Shiva and Vishnu in the city. But I never ever saw him visiting there, while he was a regular visitor to the Pagoda.

Since childhood, I had a deep reverence for Lord Buddha. This was because of the traditional belief that he was an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. But as I grew up, I only heard criticisms of his teachings such as his denial of the existence of soul and God. I feared that, under the influence of his teachings, I too might become an atheist and be condemned to hell. His teachings exaggerated misery so much that there seemed to be no place for happiness. I had also heard that his teachings strongly advocated non-violence which was responsible for debilitating our nation. Under the influence of Lord Buddha’s teachings, Emperor Asoka laid down his arms after the Kalinga victory and disbanded his huge/big army. As a result, our nation became weak and attacks/raids from foreigners increased. I used to hear many such hostile remarks against his teachings. Hence, despite a deep personal faith in him I considered it proper to keep myself away from his teachings.

Later in life, when I had severe attacks of migraine every fortnight, I was given a sedative injection of morphine as its cure. This unpleasant situation kept on worsening day by day. Then, family doctors cautioned me that I could become an addict to morphine. They said, ‘if this happens, then you will have to take a morphine injection daily.’ They advised me to consult the leading doctors of the foreign countries I visited on my business. They also said that even if they were not able to cure this special type of migraine, they might prescribe an alternative painkiller. I agreed to their good advice and the next time when I went abroad, I consulted the leading doctors in Switzerland, Germany, England, America and Japan. But I failed to get any relief from either migraine or morphine. When I returned home extremely disappointed, a very close friend of mine named U Chan Htoon, the Attorney General of Burma advised me to sit a 10-day Vipassana course. He was confident that practicing Vipassana would definitely free me from migraine. He maintained that the illness is psychosomatic i.e. related to the body and the impurities of the mind and that the Buddha’s teaching of Vipassana would purify the mind of the impurities and I would for ever get rid of migraine and its antidote-- the sedative morphine.

U Chan Htoon always wished me well and thought of my welfare. But it was unacceptable for me to practice the teaching of the Buddha, which would lead me to hell. So I hesitated to sit even if it meant enduring the migraine. When I did not heed his advice, he insisted on my meeting the Vipassana teacher at least once. I accepted his advice, as there seemed to be no harm in meeting him.

I had the impression that the Vipassana teacher would be some renowned Bhikkhu but I was surprised to know that he was U Ba Khin, the Accountant General of the Burmese Government. I was more surprised to know that the teacher of Vipassana meditation was a householder and a Government officer. Owing to my dear friend’s persistent entreaties, I went to him and found him to be a calm and saintly person. He spoke to me very affectionately. In those days, I was the President of the All Burmese Hindu Central Board. Hence, he was well aware that besides being a prominent businessman, I was the leader of the Hindus residing in Burma. As soon as I sat down the first thing he said to me was that Vipassana is practiced not for curing any physical illness and said further, ‘ If you wish to come to me to cure your migraine then please don’t come. If you wish to purify the mind of its impurities, you are welcome.’ Noticing my hesitation to join a course on account of my being an orthodox Hindu he affectionately asked me, “Is there any objection to morality in your Hindu religion?” I replied, “What to talk of the Hindu religion, there can be no objection to it in any religion.” He then said, “In Vipassana, we teach to observe moral precepts i.e. we teach Sila. But, how can any one practice morality, when his mind is not under his control. So to have mastery over mind, we teach how to achieve concentration of mind (samādhi). Is there any objection to practicing samādhi in Hindu religion?”

Since childhood, I had been listening to stories of this hermit and that sage going to the forest for practicing samādhi. For a householder like me, I thought whether it was possible to practice samādhi. Then I replied, “We are not opposed to practicing samādhi.”

He then explained that most of the techniques of samādhi help in concentrating the mind at the surface level only thereby making it peaceful and pure to some extent. But these do no help in removing the impurities lying deep in the unconscious mind. As a result, off and on, any one of them raises its head, defiles the purity and disturbs the peace of mind. Such samādhi techniques hardly benefit the meditator.

Hearing that, I recalled how sage Viśvāmitra fell a prey to the charms of beautiful Menaka and forgot his solemn vow of chastity, despite practicing severe penances. This also reminded me of the hermiy/ascetic Parashar, who was overpowered by lust upon seeing the gorgeously beautiful Matsyagandha who was rowing a boat. I was also reminded of how sage Durvasa would frequently get furious upon encountering a little unpleasant situation.

So thinking I wanted to hear more attentively what U Ba Khin had to say next. Then he said, “Vipassana is not limited to samādhi only. We go further and teach how to attain prajñā (wisdom) which will uproot the latent impurities accumulated in the depths of the unconscious mind. Is there any objection to prajñā in the Hindu religion?”

I was thrilled to hear the word ‘prajñā’. I used to recite the Bhagvad Gītā not merely out of devotion but also I was greatly fascinated by the greatness of ‘sthitprajñatā’ extolled herein. The Gita declares that he is a ‘sthitprajña’(established in wisdom) who is free from greed, fear and anger (vīta-rāga-bhaya-krodhah). Whatever is explained through ‘sthita-prajñasya kā bhāṣā’ has not only always fascinated me alone but also every reader of the Gītā. Influenced by this ideal of being established in wisdom I praised it highly and held it in high esteem. Whenever on one or other festive occasions I was invited by one or other of the Hindu religious institutions in Rangoon to speak I would always give a discourse on ‘sthitaprajñatā’ as defined in the Gītā. But returning home after every such discourse, I would be sad to know that I did not even have a trace of such ‘sthitaprajñatā’. I did not have the qualities of a person established in wisdom. Why should a person like me who has passion, anger and ego give a discourse on ‘sthitaprajñatā’? So when U Ba Khin said that he would teach me how to become established in wisdom, my heart leapt up with joy and I instantaneously agreed to sit a course at least once, not to get rid of migraine but to seek deliverance from the impurities of the mind through prajñā (wisdom)

My teacher was delighted to hear this and I went to his centre to join a Vipassana course. As I reached there, I found a small booklet entitled, ‘Do not believe’. When I went through it I came to know that the Buddha has said it. He very clearly said that one should not believe in any thing, what is hearsay or written, what is traditionally accepted or what is written in a scripture or even something which appears logical. It was further said that one should not be carried away by the speech of a handsome and impressive orator. Lord Buddha himself was very handsome and was a very good orator. This applied even to him. What he actually meant was that one should not believe even what he says.

I was astonished to read that even a great Dhamma teacher like Lord Buddha says not to believe in what he says. What actually does it mean? And when I read further I soon realized that he gave importance to one’s own experiential knowledge not to his blind belief. He said that only when you experience the truth as it is at the experiential level and see for yourself that it is beneficial for you and others then only you should accept it. And then not merely accept it but apply it in your life. This alone would be truly beneficial. Reading this, I was fully convinced that there is nothing superstitious here, nothing that is born out of blind belief.

Thus convinced, I sat a ten- day course. As days rolled by one after another I realized that the technique relied solely on the experience one has from moment to moment, on direct experience of truth and truth only. How could I ever object to this technique based on the truth?

Upon completion of the course, not only did I get rid of morphine injections but also from the migraine forever. I was wonder-struck as to how this could happen? Was it a magic or a miracle? But as I continued practicing meditation regularly, it dawned upon me that I had attacks of migraine only when some gross impurity arose in my mind. Now that I was free from defilements how could migraine recur?

Deliverance from migraine was not the only reason for me to practice Vipassana for ever in the future, but when my dreadful enemies like anger, passion and ego started receding /melting, then I accepted this technique for ever because of my great progress and achievement.

Later when I had done a few courses, I was fortunate enough to sit at the feet of my teacher for 14 years and delved deep into the ocean of Vipassana. I also followed his instructions and studied the original words of the Buddha at the same time.

Prior to this, I was greatly opposed to the teachings of the Buddha. Whenever my friend Venerable Bhikkhu Ananda Kaushalayana used to visit Burma, he would stay at our residence. He was a great Hindi scholar. He was also so humorous that I used to relish his company. But whenever he would begin to speak about the teachings of the Buddha, I would avoid him without being discourteous to him. I never heard attentively what he said about the teachings of the Buddha. Once he presented to me a copy of the Dhammapada and said that I must read it. The book lay unread on my table for three years. How could I read this? It contained the words, which were against my Dhamma?

But after practicing Vipassana, my teacher asked me to go through the teachings of Lord Buddha. Then, for the first time, I went through the Dhammapada. As I read it for the first time, I became ecstatic. Each verse of the Dhammapada was like nectar to me.

How can I forget the benefit I derived from my teacher? He gave me a new life. The jewel of Dhamma he gave me did not only do me good but also it did good to all my Indian friends in Burma who practiced Vipassana at my advice. Now, following my teachers’ instructions, I have become his Dhamma son and I teach Vipassana to many miserable people of the world. They are also deriving benefit from the true dhamma. Seeing this achievement I become ecstatic with infinite veneration and gratitude towards my most revered Teacher.

Whosoever has benefited from this invaluable technique sent to India and abroad by my teacher, it is quite natural that they feel extremely grateful to Sayagyi U Ba Khin. In this lies their happiness! In this lies their well- being!

Memories by other meditators

Ever since I read a booklet containing lectures on Buddhism delivered in 1952, I had admired Sayagyi U Ba Khin. In 1956 or thereabouts I was able to visit the annual meeting of the Vipassana Association of the A.G.'s office held at I.M.C., to present a magazine published by the Rangoon University Pāli Association and to speak with Sayagyi for awhile.

Sayagyi seemed to notice my interest in his lectures on Buddhism. He said, "You are a writer and a theoretician and I am a practical man. So it is very difficult for me to explain the practice of meditation. Come and practice it yourself and you will get a better understanding than my explanation."

Sayagyi served concurrently as officer on special duty, trade development minister, chairman of the state agricultural marketing board, and member of the advisory board of the national planning commission. Foreigners hearing of these splendid achievements often raise the question: "Where do you get such energy from?" The following was Sayagyi's reply: "Because I practice Buddhist meditation, I can handle many important tasks simultaneously. If you want to purify your mind and be happy, healthy and energetic like me, why don't you make an attempt to take a course in Buddhist meditation?"

-Maung Ye Lwin, excerpted from an article appearing in the Burmese magazine "Thint Bawa", December 1960

* * *

I doubt whether an ordinary being can point to so many periods in his lifetime that further his inner development as much as these ten brief days under your guidance. No doubt due to my insufficient pāramīs (virtues from the past), my achievements here may have fallen somewhat short of what they could have been. By perseverance I hope, however, to improve. And I already take back with me considerable added strength and composure.

You yourself are the finest example of what you set out to obtain in your pupils. Your wisdom, your tolerance and patience, and your deep, loving devotion leave a profound impact on the personalities of those who come and sit at your feet. To yourself and to your dedicated helpers goes my true gratefulness.

-from a letter to Sayagyi from Mr. Eliashiv Ben-Horin, former Israeli ambassador to Burma

* * *

My wife and I first met U Ba Khin in 1959. In all his Buddhist devotion, there was none of that searing intensity or dry, brittle hardness that sometimes accompanies strong religious conviction. For U Ba Khin was genuinely and delightfully human. He loved the roses about the centre and watched the growth of a special tree with pride and joy. It was a wonderful experience to hear him tell various of the Buddhist stories. He told them with hearty and humorous enjoyment, but there was no mistaking the depth of his feeling for them and his devotion to their truth. His experience was profound enough that it could afford the reverent joke without fear of offence. And his genuine authority as a meditation master came from this same depth of experience. There was no need for a superficial "cracking of the whip."

Thus when I think of him now, it is as a man who was eminently sane and finely human in a universal sense; who could be completely Burmese, thoroughly Buddhist, and intensely human all at once, without confusion, pretension or strain.

-Dr. Winston King, former professor of history and philosophy of religion, Grinnell College and Vanderbilt University, USA

* * *

Before the ten-day course was over, I knew that my most deep-lying fear was that my own body would perish and rot away, forever gone. I could not face death with equanimity. Sayagyi's help was essential in this crisis. Then, instead of being through with the whole thing and regarding it as an "interesting Burmese experience," I found myself coming back for another course while my husband had to be away on business, and then later for still another, before we left Burma to return to the U.S. I did not decide that Sayagyi should be my teacher. Rather, I discovered that he was my teacher.

Since that time I have not ever been out of touch with him. He has never failed to help me. And even with his death I cannot feel out of touch when I remember so well what he taught and was. His healing generosity and compassionate interest in all human beings, he learned only from the Enlightened One. He embodied that which he constantly taught to others-the calm centre in the midst of anicca.

-Jocelyn B. King, USA