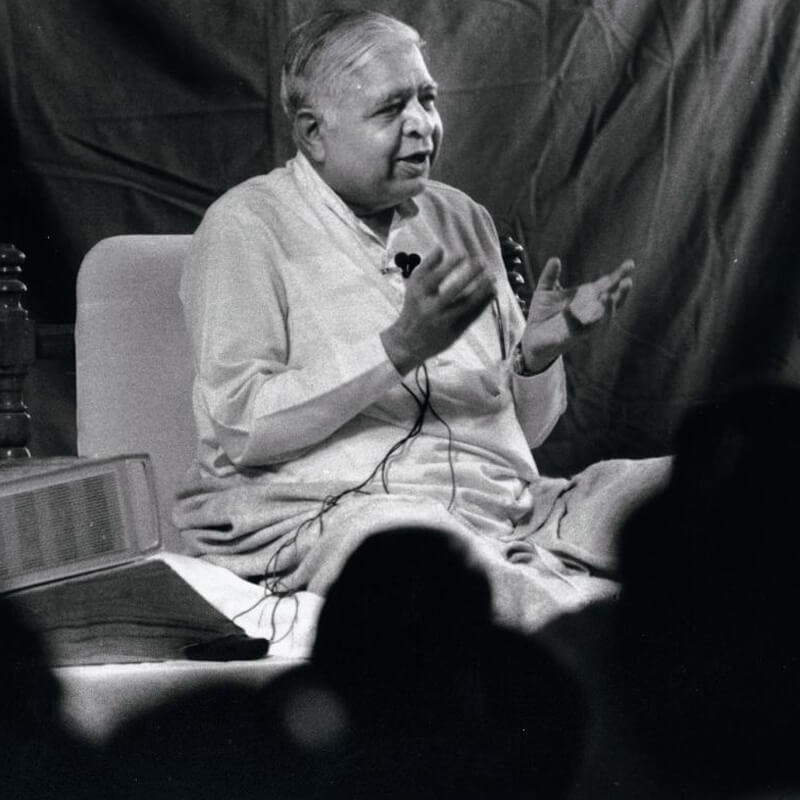

Goenkaji has often told the story of how he came to India in July of 1969. The immediate reason was to help his ailing mother by conducting a Vipassana course for her benefit. In addition, however, Goenkaji’s teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin had long wished to travel outside of Burma, to re-introduce the Vipassana technique in India and bring it to countries where it had never before been practiced. In this way he hoped to fulfill the prophecy that 2,500 years after the time of the Buddha, the Dhamma would experience a resurgence and spread around the world.

On one occasion U Ba Khin had accepted an invitation to teach abroad, and had fixed dates for courses in India and America. In the end, however, travel restrictions prevented him from leaving Burma. For this reason he saw Goenkaji’s visit to his mother in India as an opportunity to fulfill the traditional prophecy. In a formal ceremony he authorized his student as a teacher of Vipassana meditation, and shortly afterward Goenkaji embarked for India.

Naturally, Goenkaji shared his teacher’s hopes. He was eager to serve his mother and father as well as other people who wished to learn Vipassana meditation. At the same time he did not realize that the journey on which he was embarking would last decades. He knew few people in India, and regarded Burma as his beloved homeland. He confidently expected to return there within a few months.

The Wheel of Dhamma had started turning again, however, and Goenkaji had to extend his stay in India indefinitely in order to meet the surprisingly strong demand for Vipassana courses. With at first virtually no old students and organizational support to help him, he traveled from one end of the country to the other, giving courses in rented sites and gradually laying the foundation for the rebirth of Vipassana in India. His efforts have borne abundant fruit: today there are four Vipassana centers in India, and tens of thousands of meditators from every walk of life.

Re-establishing the practice of Vipassana in India was still only a part of his mission. Another part was to help it spread around the world. From the very beginning people from western countries had joined Goenkaji’s courses, and many of them were eager to see courses held in their own lands. One of these students—a woman from France— invited Goenkaji to come and conduct courses in her country. Goenkaji explained that he had taken a decision for the first ten years to confine his teaching to India, so as to build a firm base there for the spread of Vipassana. But he promised that France would be the first western country where he would hold courses. “Come back and ask me again when ten years are over,” he said.

In fact there was a second reason that kept Goenkaji in India. When he had left Burma in 1969, he was issued a passport valid only for travel to India. Because his family was originally from there, he could of course easily receive Indian citizenship, and would then be able to travel freely. But he was reluctant to sever his links with the land that had given him birth and Dhamma. For this reason he made repeated requests to the Burmese authorities to grant him travel endorsements for other countries. If after ten years he had still not received a positive response, he would accept the inevitable and change his nationality for the sake of the Dhamma.

The years passed quickly, filled with Dhamma work and achievement. As they approached their end, the same student again contacted Goenkaji, this time with a formal invitation from the European Federation of Yoga Teachers, to conduct courses under their auspices in France. Goenkaji accepted their invitation, and students in other western countries made plans for further courses to follow the ones in France.

The problem of his passport still remained, however; the Burmese government had not given him permission to travel outside India. At last Goenkaji decided to apply for Indian citizenship, although he knew that this action might be viewed as disloyal by some Burmese, and might bar him from ever returning to his motherland. He could only hope that one day the Burmese government would realize that he had acted in a noble cause: to make the jewel of Dhamma, long preserved in Burma, more widely available in the world. Finally, in June 1979, he became an Indian citizen. He received his new passport hours before his departure for France.

On July 1, Goenkaji’s first course in a western country began at Gaillon, in Normandy, France. The site was a chateau that had been converted into a luxurious vacation hotel; the Yoga Federation customarily held meetings for its members in such luxurious accommodations. Quite a few old students who had sat with Goenkaji in India came for the course. Most of the students were members of the Yoga Federation and there was almost no management; cooking was done by the hotel staff. The discipline was much laxer than at centers in India.

Language presented a major problem. Taped French translations had been made of Goenkaji’s discourses, but the recording quality was not good enough to use for a large group. As for the meditation instructions, no French versions existed. The only way to proceed was with the help of old students who acted as interpreters: Goenkaji would speak a few sentences in English, and the interpreter would repeat them in French. Interpreting is always a stressful task; to perform it in the context of a meditation course was all the more difficult. The students had to work in teams, one relieving the other when the pressure became too great.

There were other difficulties, not all unexpected. Any major advance in the spread of the teaching of liberation, Goenkaji explained, is bound to encounter obstacles. Overcoming these was a way of gaining strength. Gradually a meditative atmosphere was established, and participants in the course were able to appreciate the technique of Vipassana.

At the end of this first course, Goenkaji stayed overnight in Paris. Like most tourists, he asked to visit the Eiffel Tower. His purpose, however, was not to admire the view from the top, but to distribute mettā to all the inhabitants below.

A second course followed at Plaige, near Lyon in central France, after which Goenkaji flew to Montreal, Canada, to conduct his first course in North America. Unlike the courses in France, this was organized and managed by a team of Vipassana meditators. The site was a boarding school in the suburbs of the city. Approximately 185 people participated from all parts of the North American continent. Many of them were old students who had started meditating with Goenkaji in India in the early 1970’s, but had not been able to sit with him since. Despite a heat wave and extremely limited outside walking areas, the meditators worked hard, and Goenkaji was very pleased with the course.

Next Goenkaji traveled to Britain for two consecutive courses, again organized by meditators and attended by people from all over Europe. At these courses the evening talks were videotaped for the first time. Although the tapes have never been widely used, they marked the first time Goenkaji’s teaching had been recorded in this way.

The entire tour covered two months during which five courses were held in three countries with over 640 participants. More important, however, the 1979 tour laid the groundwork for the spread of Vipassana in western countries. Meditators developed the skills to plan, manage and (perhaps hardest of all) cook for large courses at rented sites. They also began to form the organizational structures that were necessary for offering regular course programs and for founding centers. The work of translation of the teaching into other languages and of recording Goenkaji’s words both received fresh impetus. It became clear that all these tasks, and many other related ones, can and must be undertaken by dedicated old students wishing to help others experience the benefits of Vipassana meditation.

Most important, the 1979 tour gave renewed inspiration to western meditators. For those who served, it was deeply moving to see their efforts assist in the transmission of the teaching in their homelands. For many, the tour was a chance to meditate again with their Dhamma Father, and to revitalize their practice. For all, it demonstrated that the Dhamma is indeed universal, transcending cultural boundaries and offering a way out of suffering.

Recollections

The following are from students who attended Goenkaji’s first courses in the west.

July 1979 : Goenka's first course in France, at Gaillon. What wonderful memories. First of all, a magnificent site and perfect weather. But above all, in the sparsely furnished old barn, the wonderful discovery—like two plus two equals four—of Ānāpāna and then Vipassana, taught by this man who was at the same time so simple and so disciplined. We were about 60 people. We were all new to the technique, but so full of good will!

When the meditators came to sit before Goenka, I could hear their questions and his answers. For example, a lady said, "In the last sitting I had a pain in my heart. It was so sharp I thought I was going to die." Goenka replied, "Has it passed now?" "Yes." "Good," said Goenka. The woman seemed stupefied by this answer. Seeing this, Goenka added: "Why? Would you have liked it to continue?"

I lived intensely those ten days, experiencing pain, tears, despondency, joy, deep inner silence, and moments of great happiness. I was 62 at the time. As a young man, I had been a Trappist monk for 13 years. When the course was over I said to myself, "Goenka has just taught me in ten days what the Trappists could not teach me in 13 years!"

* * * * *

For years some of us had divided our lives between home, family and work in the west and the Dhamma in India. Of course there were meditation activities around the world, but they lacked the impetus of Goenkaji's presence. His first visit seemed like a new beginning, when anything might happen.

Students had to be warned not to create mob scenes by gathering to greet him at airports on arrival or departure. He wanted no undue attention. Still it was a thrill to watch him arrive in Paris—one of the first times I'd seen him in a business suit—accompanied by Mataji in sari, of course. He was smiling broadly, eager to begin the new stage of his work.

I had served on courses at Dhammagiri and knew a little French, so I offered to help on the first course in France. I started by doing the usual things a course manager does: making signs and ringing bells for sittings. To my surprise, these awoke quite violent reactions; one day someone even hid the bell! Many of the members of the Yoga Federation had evidently joined the course without knowing much about it. They expected a pleasant holiday with friends in a deluxe hotel, with a few meditation classes thrown in. They were not at all prepared for such basic aspects of a Vipassana course as silence, cutting of contacts with the world outside, or regular attendance at group sittings. I kept running to Goenkaji to report on new breaches of discipline. The worse it got, the more upset I became.

In those days in India, Goenkaji used to alternate giving the Dhamma talks in Hindi in one course and in English in the next. Participants in Hindi courses were mostly Indians, while westerners made up the majority in English courses. It was noticeable that the discipline was looser on Hindi than on English courses; this was simply a cultural difference that we had to accept with a smile.

Now in France, Goenkaji reminded me of this. "Just pretend it's a Hindi course," he told me. The important thing for him was not that each rule be folllowed, but that the seed of Dhamma be planted.

* * * * *

Each evening of the course in Montreal, the managers would report to Goenkaji in his room on the day's events. He was in wonderful spirits, very pleased with the course, and bubbling over with stories and anecdotes. The new beginning in the west must have recalled to him his early days in India, and he reminisced about them. In those first courses when U Ba Khin was still alive, Goenkaji would report to him in detail on each course and each student's progress. Sayagyi was delighted at the large numbers coming to learn Vipassana. In one of those early courses there were 37 students. As Goenkaji told us, Sayagyi was very pleased: "An excellent number," he said; "thirty-seven for the thirty-seven factors of enlightenment!" When the first course of 100 students was held, Sayagyi was still more pleased, and told all the visitors to his center in Rangoon about it. It must have seemed to him that, as he said, the hour of Vipassana had indeed struck. How happy he would have been to see hundreds of people around the world now coming to learn the Dhamma.

* * * * *

The Montreal course in 1979 was my first course with Goenkaji. I flew 3,000 miles to be there. The school where it was held was in what seemed to be a poor district of the suburbs. The exercise yard was about the size of a three-car garage. It was separated from the street by a chain link fence. Walking in it you felt like you were trapped in a small cage. The neighbors used to hang on the fence and watch us while we were walking. None of the meditators spoke—I felt like a monkey in a zoo. All the facilities were for kids: the water fountains were 2 feet high, the chairs were 3/4 size; the toilets and sinks were for people who are 4 feet tall. The meditation hall was a huge, miserably ventilated gymnasium. It was stifling hot; some of the people in the back rows where I was sitting passed out.

Every day we heard the same sounds, of teenage residents of the neighborhood squealing their automobile tires. One day later in the course, on day 6 or 7 when people were getting lighter, during a pause when the hall was quiet, we could distinctly hear someone jump into his car, slam the door, screech out of the driveway, brake suddenly, then crash into a trash can, which bounced down the street. The room erupted in a chorus of laughter.

There have only been two times in my sitting career of 11 years when I have felt the need to go to the teacher for guidance. One was on this course. I was experiencing intense rage. I was boiling with anger; I was murdering people in my mind. I didn't know what to do about it—I thought meditation was supposed to make you peaceful. I went to see Goenkaji. He was sitting in a beach chair, with his legs crossed. It pleased me to see him so casual. He listened and laughed and said, "Yes, yes, yes. This shows that the technique is working perfectly. You'll probably have some violent dreams." He was right. I did have violent dreams, and as a result of the course, that particular sa%khāra of acute anger passed. I've had other problems, but I've never had anything like that happen again. I cleaned out a lot although I didn't realize it at the time. A big chunk of emotional trauma just stopped happening. I found the course in retrospect to be very healing.

* * * * *

Some friends of mine flew from the west coast to Montreal to sit Goenkaji’s first course. Montreal and this teacher from India seemed remote to me. When my friends returned, one of them said, “Goenka is a businessman. When I had an interview with him, he got straight to the point, and didn’t let me dawdle in long-winded philosophizing. Since I’m a businessman too, that appealed to me." Another friend said, “It was one of the most significant steps I have taken. I think you should try it.” Someone else warned, "The discipline was really rigorous.” This scared me, and I had reservations about attending the course in California the following year. But I went, and happily completed the course. Rather than being the barrier I had feared, the strong discipline was an enormous help. It helped enable me to meditate deeply. I’ve been sitting every day since that retreat. It is miraculous to think back to those first western gypsy camps a decade ago, to reflect on how quickly and widely the Dhamma has spread since then.

(Courtesy: International Vipassana Newsletter, Vol. 16, No. September 1989.)