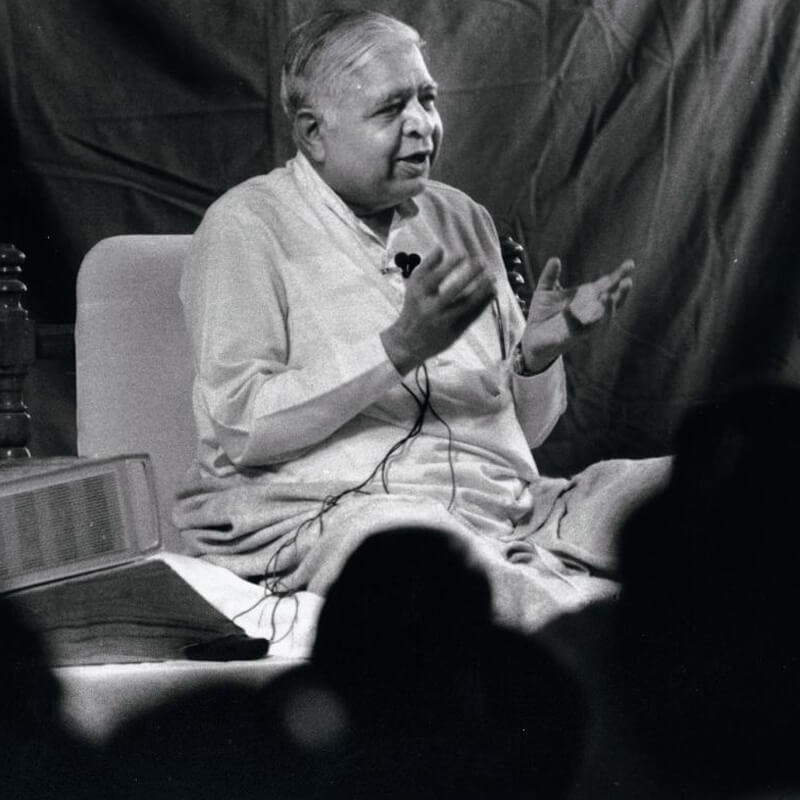

(Following discourse was given by Mr. S. N. Goenka)

Compassion (karuna) is a very noble state of the human mind. Like selfless love (mettā), sympathetic joy (mudita) and equanimity (upekkha), compassion is also abrahmavihara (sublime state of mind). Merely talking about compassion, discussing compassion or praising it-all these are far away from true brahmavihara. It is good to accept compassion at the intellectual level as an ideal sublime state. But this is also far away from true brahmavihara.Brahmavihara means the nature of abrahma (the highest being in the order of beings). It is the practice of superior qualities, the practice of Dhammic qualities. Only when the mind is suffused and overflows with suchbrahmic qualities can we call it brahmavihara. The mind can overflow with compassion as well asmettā, mudita and upekkha only when the mind is completely free from all defilements at the deepest level. This purity of mind and the resultant sublime states born out of it is the fruit of practice of Dhamma.

What is the meaning of living a Dhamma life? It means living a life of morality, that is, to abstain from performing any vocal or physical action that will disturb the peace and harmony of others and harm them.

In order to get established in morality it is necessary to have complete control over one's mind. The mind should be fully restrained, fully disciplined. For this, it is necessary to practice concentration of mind with a neutral object of meditation. A neutral object of meditation neither generates raga (attachment) nor dosa (aversion). It is based on direct experiential truth and is free from ignorance.

But it is not enough to concentrate one's mind with the help of such a neutral object of meditation. It is necessary to develop wisdom (pañña) at the depths of the mind on the basis of direct experience and to become established in this experiential wisdom (pañña). By this practice it is possible to eradicate the ingrained habit-pattern of the mind that generates, multiples and accumulates reactions (sankharas) of craving and aversion out of ignorance.

As the wisdom gradually weakens this habit pattern, the old accumulated defilements are eradicated and new ones do not arise. Ultimately, the mind is completely freed of all defilements and becomes pure. Then the mind is naturally filled with the brahmic qualities of mettākaruna, mudita, and upekkha.

As long as the old stock of defilements is present in the mind and new defilements are added to it, it is not possible forbrahmavihara to arise in the mind. Ego plays a role in the arising of all defilements. As long as the mind is ego-centred, self-centred, one may talk about the four brahmaviharas and praise them highly, but one is not able to cultivate true brahmavihara.

The more the mind becomes free from defilements the more the development of brahmavihara. When a meditator is fully liberated, he dwells continuously in the pure brahmavihara. Therefore, for development of the brahmaviharas of mettā.

karuna, mudita, and upekkha, it is absolutely essential to become established in sila, samadhi and pañña.

No individual of any caste, colour, class, society, community or religion has a monopoly on the practice of sila, samadhi and pañña. The practice is universal. Anyone can cultivate them by exerting sufficient effort. One who cultivates them and purifies his mind becomes naturally suffused with love, compassion and goodwill. Just as the defilements of an impure mind cannot be labelled as Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist and Jain defilements, similarly love, compassion, goodwill and other wholesome qualities of a pure mind cannot be given any sectarian label. The defilements and wholesome qualities of the mind are the same for all.

Just as the pure Dhamma of sila, samadhi and pañña is universal, eternal, absolute, timeless all over the world, so also the brahmavihara arising because of its practice are universal, eternal, absolute, timeless all over the world. None of the religious traditions-Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Sikh, Muslim, Christian, Parsi or Jewish-reject the importance of morality, concentration of mind and purification of mind, and the resultant compassion and goodwill.

Different societies, communities and sects have different ways of worship, different places of worship, different rites and rituals, different festivals, different vows and fasting days. Their philosophical beliefs are different. Actually, different communities or sects originate and flourish on the basis of these differences. But the Dhamma of morality, concentration, wisdom, and love, compassion and goodwill is universal. It is the same for all societies, communities and religions. This universal Dhamma and the resultant compassion unite all religious sects. While continuing to maintain their distinct sectarian features, they can unite at the level of universal Dhamma. All can become one in the practice of the brahmaviharas of love and compassion.