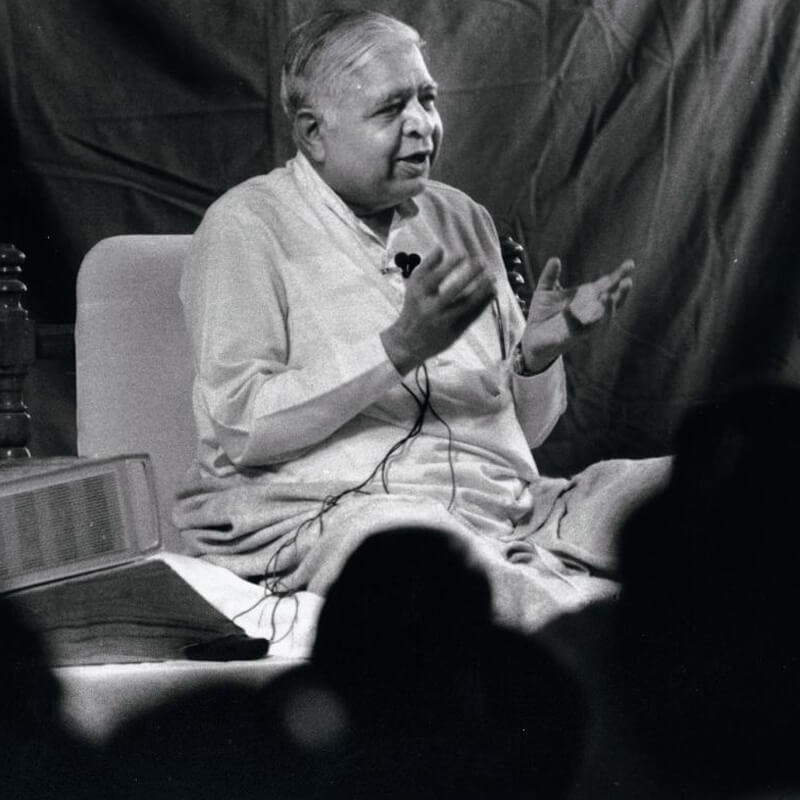

(Following Public Discourse was delivered by Mr. S N Goenka in Mumbai on the occassion of Jain Celebration in 2005)

Ladies and gentlemen,

You have all assembled here to learn about Dhamma. This shows you all have a keen interest in it. So let us understand what Dhamma is.

At first you need to understand it at the intellectual level, but actually Dhamma can only be truly understood when it is lived in life, only when it is practiced. But initially it is necessary to listen to somebody explain it and try to understand it at the intellectual level. Then a stage will come when it is practiced.

To listen to discourses is not really Dhamma, nor is reading the scriptures or going to the temple Dhamma, but when you experience it, then it is Dhamma.

‘Dhārana kare so Dharma hai, varanā korī bāta;

Sūraja uge prabhāta hai, varanā kālī rāta’.

— Dhamma not experienced, not lived in life is useless. The dense darkness of night is removed only when the sun rises.

We may go on praising the sun and its light, but until it rises in the sky the night will remain dark. In the same way Dhamma cannot be properly known unless it arises within ourselves.

The great men of our country have explained Dhamma succinctly. Lord Mahavir said that in Dhamma lies the great welfare of mankind, not the ordinary one. But when does it bring a great result? Only when it is lived in life. He further said that practicing non-violence, self control and doing hard work is Dhamma. Otherwise it is only a verbal and intellectual revelry, which cannot bring us even ordinary welfare, let alone our highest welfare.

Another great man of our country has said the same thing, but in a different way keeping in mind the audience before him. Instead of non-violence, self control and hard work, he said that Dhamma is developed in three steps of morality (sīla), concentration (samādhi) and wisdom (paññā).

Sīla

Generally speaking when we kill a living being, it is considered violence, when we abstain from killing, it is non-violence. Let us understand this at a deeper level. If we deprive somebody of peace and happiness it is also violence, if we do not do so it is non-violence. This is the first moral precept.

The second is that we should not steal or forcibly snatch away something dear to someone, realizing how painful it will be for those who will be deprived of their possessions and their peace and happiness.

The third is indulging in sexual misconduct. By committing adultery we cause suffering to others. This is also violence because they are robbed of their peace and happiness.

The fourth precept is not to tell lies and not to speak harshly. When we tell a lie and cheat people we rob them of their peace and happiness and when we speak harshly to others and make them agitated, again we rob them of their mental peace and happiness. All such actions come under violence. One commits acts of violence not only when one kills somebody but also when one deprives others of their peace and happiness. These are called moral precepts, good conduct or Cāturyama—four restraints. However, only believing that these precepts are good will not suffice, one must practice them in life for them to prove to be beneficial. A fifth moral precept was also added, which is to refrain from indulging in drugs and alcohol or any kind of intoxicant. Even though one understands that one should not deprive others of peace and happiness, one will possibly indulge in sexual misconduct, or tell lies or speak harshly when in an inebriated state without realizing what one is doing, and thereby hurt and harm others. The first four are important aspects of sīla, while the fifth is also no less important.

When one lives according to the laws of Dhamma then benefits will arise. One who hears Dhamma but does not practice it is like a sick person who instead of taking the medicine prescribed by a doctor after an examination, keeps on repeating what is written on the prescription – 2 tablets in the morning, 2 at noon and 2 in the evening. Will this heal the ailment? Certainly not! The medicine has to be taken; only then will it cure the disease. Dhamma too has to be imbibed, it has to be lived, then alone will it give its benefits.

Samādhi and Paññā

In order to live Dhamma it is necessary to discipline one’s mind in order to concentrate it. This second step is called samādhi. We know very well what should or should not be done, yet we often end up indulging in wrongdoing as we have little control over our minds. Even though not addicted to drugs or alcohol, a person may be addicted to anger, desire, arrogance. The intoxication produced by these defilements may even be stronger than that produced by alcohol and drugs. Under the influence of these defilements and without really meaning to be violent one may end up killing somebody or depriving people of their peace and happiness. Hence samādhi, or disciplining of mind, is of great importance but even this is not enough. We may not commit any verbal or physical violence, thereby depriving others of their peace and happiness, but if we deprive ourselves of peace and happiness this also is harmful.

We must understand that any defilement that arises within, be it anger, animosity, jealousy, arrogance or desire, results in producing an imbalance of mind. Then peace, happiness and equanimity are lost. This is harmful because a person who loses his or her equanimity due to defilements causes agitation and unhappiness all around. At that time all those who come in contact with this person also lose their peace and happiness. So we need to understand that when we become agitated we make others agitated, and consequently the whole atmosphere is disturbed.

To address this we come to the third step—called tapa. We have forgotten its real meaning. Tapa is not practicing external austerities. It is experiencing what happens in the depth of one’s mind where defilements arise, multiply and make us so blind that we do what we should not, and do not do what we should.

This is called wisdom (paññā) in some traditions. Not the paññā that consists in book learning and using logical acumen, but the paññā which develops from directly experiencing what happens in the depth of one’s mind. In olden times in India this was also called prajñā.

Now that most of the ancient learning is lost, the real meaning of prajñā is also lost. These days the word is only being repeated and recited. As a result of this people think they are getting established in wisdom, but paññā has to be developed through direct experience and they have forgotten how to develop it.

When a person for instance gets angry, the total chemistry of the body changes; heat, agitation and stress are generated, the heart-beat becomes rapid. This person may justify his anger saying that the other person behaved in an undesirable way so he is angry with him and needs to take revenge on him, punish him, make him unhappy and so on. Little does he realize that by so doing he is only making himself unhappy.

It is the immutable law of nature that a person cannot make others unhappy without first making himself unhappy, he cannot deprive others of peace and happiness unless he first deprives himself of these. If a person thinks of killing someone, anger and hatred will arise in him first which will cause him misery. If he thinks of stealing, greed and craving will arise in him; if he thinks of committing sexual misconduct, passion will arise in him; if he thinks of telling a lie and speaking harshly, greed and arrogance will arise in him. One cannot commit vocal and physical unwholesome actions without first being influenced by various defilements. The great men of our country realized this truth—A person kills himself first before he can kill anyone else. A great man is one who says something based on his experience. If one repeats what he has heard from others or what he has read in books it may sound good, but as it is not based on his experience it is not very helpful in living a Dhammic life. So long as one does not experience the truth that before killing others he kills himself, before depriving others of their peace and happiness he loses his own peace and happiness, then he cannot understand Dhamma deeply, he certainly cannot teach Dhamma.

Realizing the truth was not a mere intellectual exercise for the great men of this land. They realized this truth within, they experienced it. Just by reading books on Dhamma, or contemplating and discussing it, one does not become a wise man. In the same way we need to awaken to the truth ourselves, knowing that Dhamma is to be lived and experienced; not merely indulged in by endless debates and discussions.

True Dhamma will arise in us when we develop our awareness of the great harm the arising of mental defilements can do. So long as we do not realize this with the light of Dhamma, the night will remain dark for us no matter how much we may hear and contemplate laws of Dhamma, and immerse ourselves in rituals and vacuous competitions so as to be considered more non-violent than others. To see the truth within oneself is to be truly Dhammic.

In ancient times to see within was called vipassana. To see truly means to experience, not only to see with open eyes. What do we see with open eyes? We see colours, shapes and forms but vipassana means to experience. We have forgotten its ancient meaning which is to see, to feel and to experience the truth within ourselves.

Even today in common parlance we use the term passanā (to see) at times in the sense of experiencing. For instance when we ask someone, ‘listen to the music and see how it sounds’, or ‘eat this rasgulla and see how it tastes’, or ’touch the velvet and see how it feels’; we mean to hear the quality of the music, or imbibe the taste and sweetness of rasgulla, or feel the softness of velvet.

When we learn to see within and experience what happens when we break our sīla, we learn not to do it again because it makes us unhappy and makes us lose our peace of mind. We will never think of raising our hands to slap or abuse someone now because we realize that that will make us lose our peace of mind and make us restless.

Someone who has experienced this truth needs to use words to share this experience with others. These words, with the passage of time, will become a philosophy of which his followers become fond of. They have faith in these words so they come together, form a community and establish a sect. Often this results in struggles, ego clashes and one-upmanship among believers of various sects and philosophies, resulting in unmitigated violence. We are lost!

Truth is indeed to be experienced and not merely believed in. Anything that arises in the deeper recesses of our minds has to be experienced; if anger or fear has arisen, one sees what is happening within, not by intellectualising, but by experiencing the truth that has arisen within one’s own self. This is Vipassana.

A truth experienced by someone else is his truth. We may believe it if we have faith and trust in his words. But it is still not our truth. The day we experience it ourselves it becomes our truth; that day Dhamma will arise. True non-violence will arise. We will then know through direct experience that before killing someone else or disturbing his peace and happiness, we are killing our own selves or disturbing our own peace and happiness. This awareness is immensely beneficial as no one ever wants to make himself or herself unhappy by committing violence.

To see the truth as it is without imagining it, is meditation. We thus follow the three steps of sīla or morality, non-violence, samādhi or concentration of mind, and paññā or wisdom. We concentrate the mind by observing the precepts of morality and with this sharply penetrating mind we see the truth and learn from firsthand experience what to do to have peace of mind.

Let us take an example. A small child wants to play with hot burning coals thinking them to be toys and his mother stops him. One day his mother is not watching and he pounces and catches a piece of burning coal and cries in pain. He now knows for himself that fire burns and will be careful in the future.

Once we learn to see within, we too will know that the fires of anger and other defilements burn us. One wrongly believes that the cause of one’s anger is outside. One often thinks, ‘So and so has harmed me, insulted me and therefore I am angry with him’. But once one begins to see how one is burning within when one is angry, then one knows that one only has oneself to blame for what is happening.

My Experience

Fifty years ago I went with great hesitation to my Acarya, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, to learn Vipassana. I was under the false impression that this path was for Buddhists, not for Hindus, and as I was a Hindu I feared that I might be converted to Buddhism! These words rang in my ears—It is better to die in one’s own Dhamma than to join others’ Dhamma. I wondered what should I do!

Then a situation came that left me with no choice, and with great hesitation I went to my Guru to learn Dhamma. Of course, once I tasted Dhamma I realized what true Dhamma was! Far from sectarianism, Dhamma is eternal truth applicable to one and all.

It is above sectarianism as it is the law of nature, a universal law, (rit). For example if anger arises, one burns with anger and suffers. Nature punishes this person. This is an immutable law of nature which is applicable to all, whichever religion he or she may belong to. This has been called Dhamma in India—swabhāva dhammo—whatever its nature is, is its Dhamma. Anger is anger and it burns all. It cannot be labeled Hindu anger or Muslim anger or Jain anger or Parsi anger.

It burns all irrespective of the religion they belong to. It is a law of cause and effect. Nothing can stop this truth from manifesting itself. If you do not want the reaction that follows, then do not indulge in generating negativities and defilements. We see that when a hand is placed in fire, the hand will burn irrespective of whether the hand belongs to a Hindu, a Muslim, a Parsi, or a Sikh. The Dhamma of fire is to burn.

There is a great difference between the laws of Nature and the laws of the country one lives in. If one does not follow the laws of their country, one is punished. But sometimes it takes so long for the punishment to occur; if a good lawyer is hired one may get off scot-free. But when one breaks the law of nature the punishment is immediate.

On the other hand if one does not break the laws of nature but observes them the reward is immediate. If moral precepts are observed and one develops loving kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity one feels so happy and peaceful.

Learn to purify your minds. Learn to be free from defilements and you will see how great the peace and happiness is that you will experience.