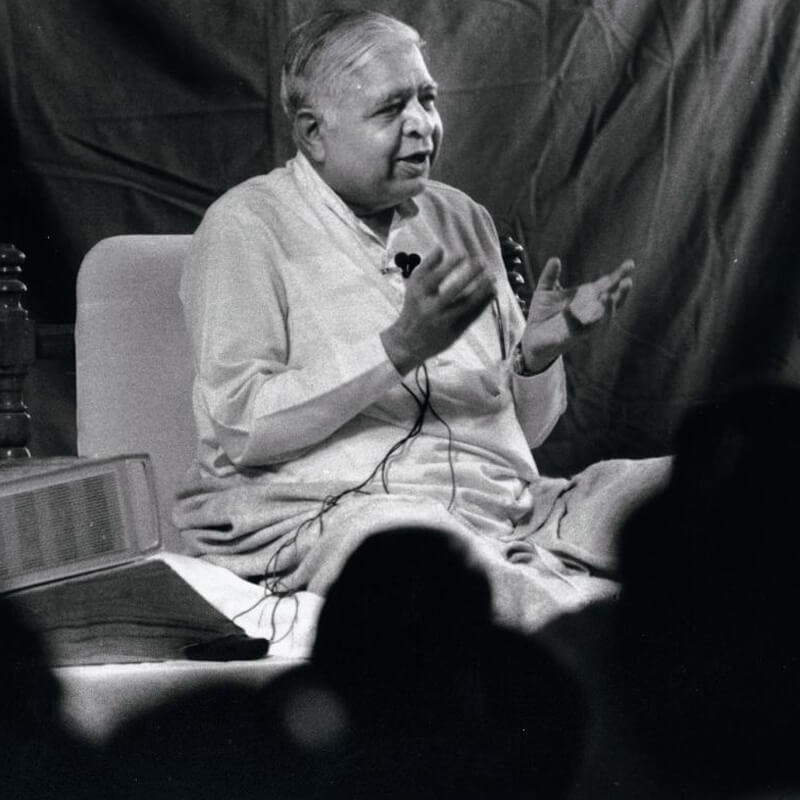

(The following article by Mr. S N Goenka appeared in the Hindi language Vipashyanaa Patrika of January-February 1985)

On 19 January, 1971 my dear Teacher, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, to whom I am ever grateful, passed away. It was always the deep wish of Sayagyi to help repay Burma’s debt to the Buddha and to the land of the Buddha, India, by reestablishing the Dhamma there in the country of its birth. He hoped that the Ganges of Dhamma, which long ago once flowed from India to Burma, could now be channeled back to the land of its source, in order to slake the thirst of millions of suffering people. A seedling from the tree of Dhamma which gives fruit in every season, had been transplanted centuries ago to Burma from India. The mother tree had withered, but the seedling had flourished and grown. Now a cutting must be taken from it and planted in the fertile soil of India, to give sweet fruit and cool, pleasant shade. And this invaluable jewel of the Indian heritage should also be shared with every land throughout the world

To realize this holy wish of Sayagyi, only a small step had been taken in his lifetime. In the fifteen years since he breathed his last, many more steps have been achieved, and if the progress at times was slow, it has been sure and steady. Now, with the gathering momentum of all these years of work, the time has come for the Dhamma to spread at greater pace. Up to now, centers have arisen in various places in India and abroad, and nearly fifty assistant teachers have started conducting courses for the good and happiness of many. Now still more courses must be offered in many more areas by more assistant teachers. Not only that, but meditators must be helped to experience the teaching at deeper levels.

I remember well my own experiences on the path. After I first learned the technique while living in Burma, I kept up a regular daily practice but had to devote much more of my time to my business and family responsibilities. Suddenly, however, there came a change in fortune: in 1964, the government took over all businesses and industries. This action, unfortunate for me in the eyes of others, was actually my good fortune, since a heavy burden was now lifted from my shoulders.

The following five years were the golden age of my life. I had always longed to study and absorb the words of the Buddha relating to Vipassana, but in the hurly-burly of active life how to find the time? Now here I was with unlimited time and with my Teacher close at hand. The result was that my practice took wing. In meditation I could go more deeply than ever before, and when I read the words of the Buddha I would feel a thrill of delight throughout my body. I felt sometimes as if the Buddha was speaking directly to me, as if every word was aimed specifically at me. At home, I would read a sutta and then go to my Teacher, who would take up certain points from it and expound deeply on them. This was a veritable shower of nectar, the nectar of the Dhamma.

Sayagyi, that incarnation of compassion, was always ready to discuss Dhamma with me. Even while sick in bed and badly needing rest, if he came to know that his Dhamma son was waiting to see him, compassion and joy arose in him and he would speak with me, explaining in depth a Dhamma text. As someone might card cotton or wool, combing out snarls and tangles, Sayagyi would remove all confusions, all ambiguities. The translations gave only grammatical explanations. But the explanation of this Vipassana yogi, this king of yogis, was of a different order altogether. He explained according to the experience of meditation, and in this way he could penetrate to the most profound meaning of the text.

His words always filled me with joy and inspiration. And then, after explaining Dhamma to me, he would tell me to go and meditate. At such a time I was able to penetrate deeply at the experiential level as well. Layer after layer of illusions and delusions would pass away, leaving the truth crystal clear. By the time I rose from meditating I would feel freed of all knots, liberated from all confusion.

From these experiences boundless gratitude would arise in me, firstly to the Buddha and then to his Dhamma sons, the chain of teacher and pupil extending link by link from the Buddha to Sayagyi U Ba Khin. To all of them I felt deep gratitude for preserving this technique in its original purity without any admixture whatsoever. At the same time gratitude would arise in me towards all those who had preserved the words of the Buddha free from any corruptions, so that today it is still possible to read them and be inspired by them. Pariyatti and patipatti—study accompanied by practice—these two seemed to me like a gem, the beauty of which is enhanced by its golden setting.

How greatly I benefited from these experiences, yet how little are such experiences accessible to meditators today! Although the Pāli Tipiṭaka has appeared in Devanagari script in India, for many years these books have been out of print. Further, whatever portion of the Tipiṭaka was translated into Hindi decades ago is also unavailable now, while little if anything has been translated into other Indian languages. Meditators in India are, therefore, cut off from the words of the Buddha.

In the West, it would seem that students are more fortunate, since the entire Tipiṭaka has appeared in Roman script and has been translated into English. But, in fact, the passages of it relating directly to meditation have presented unusual difficulties to most scholars. These passages have been translated in a way that many a time could create confusion in the minds of meditators who read them.

When students participate in courses on the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, studying the words of the Buddha while at the same time applying them in meditation, they are inspired and filled with gratitude. They feel as if the technique is revealed to them for the first time in all its brilliant clarity. Naturally they would like to study even more. How happy they would be if they could study in their own language, not only the Tipiṭaka, but also the voluminous literature of the commentaries!

It is not expected or necessary that all should be motivated to study the texts, but certainly there are many who are able and eager to do so, who could plunge easily into the ocean of the Tipiṭaka. For them the opportunity must be provided.

And not only the Pāli texts but also those in Sanskrit and Prakrit contain references to Vipassana. If a meditator undertakes the necessary research, this technique will be revealed as the essence of the entire Indian spiritual tradition.

It is a large task, no doubt, but the time has come to make a beginning no matter how small.

Doing so, however, must never be at the expense of meditation practice. Otherwise, Vipassana centers might degenerate into places where people merely read, write or talk about the Dhamma, and the real purpose might be lost. Our aim is always to experience the Dhamma within ourselves in order to emerge from all suffering. And the means to do so is the practice of Vipassana meditation. Reading, writing and study are merely to find guidance and inspiration in order to go more deeply in the practice, and thus to come closer to the goal of liberation.

Without sacrificing this object, opportunities should be created near all the centers for pariyatti, study of Dhamma. And it must begin at the main center, Dhammagiri. At the foot of the hill, on the approaches to the Academy, is a suitable place to establish facilities for the study of Pāli and for research on the original texts. All who participate, not only students but also teachers, must be regular meditators, and meditation must be an important part of the curriculum. If this is the case, their study will enable the participants to meditate more deeply and experience Dhamma more profoundly within themselves.

May the lofty example of Sayagyi U Ba Khin give you inspiration for still greater efforts in Vipassana throughout this year, for your own benefit and for the good and benefit of many.

Kalyānmitta S. N. Goenka

(Courtesy: International Vipassana Newsletter, April 1986 issue)