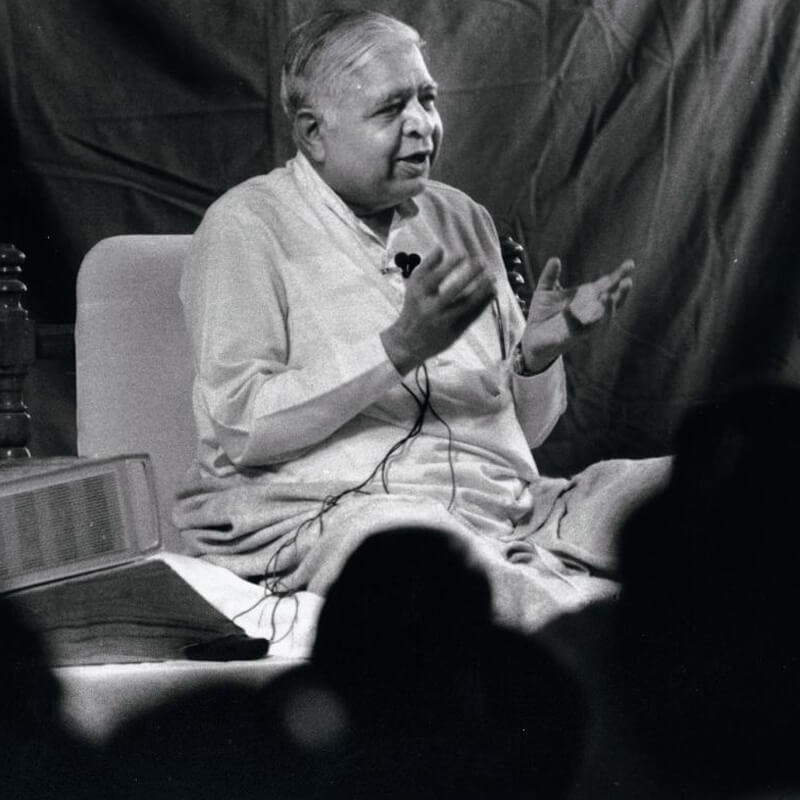

(The following has been translated and adapted from the fifth in a series of 44 Hindi discourses by Mr. S. N. Goenka and broadcast on Zee TV)

A meditator who comes to a meditation centre to learn Vipassana for ten days should clearly understand the ultimate goal of this meditation technique. Otherwise, one will get stuck at some midway station. One should clearly understand that the ultimate goal is to purify the mind, to free it completely from defilements. Dhamma is development of a pure mind. When the mind becomes pure and Dhamma becomes a part of life, one has learned the art of living. One becomes happy and helps to make others happy. This is the only aim of the practice of Dhamma. To purify the mind completely, to free it from all defilements, one will have to reach the depth of the mind where these defilements arise, multiply, and accumulate. One will have to stop their arising and multiplication at the depth and gradually eradicate the old stock of defilements so that the mind is completely purified.

Defilements arise within us, not outside. Pleasant or unpleasant situations occur outside, desirable or undesirable situations occur outside, but defilements arise within us, the resultant suffering, misery, grief arise within us. Therefore, to eradicate these defilements, one must journey within. Knowledge of the apparent truth at the surface level will not take one to the depth of the mind where the defilements arise. Beginning with very gross truths, one will have to understand progressively subtler truths of the body and mind until the subtlest truth is reached.

This must be done at the experiential level. The truth about this body and mind cannot be understood by reading books or listening to discourses. There is a vast difference between believing and knowing by direct experience. When understanding is based on actual experience, the entire secret of nature unfolds before us: how mental defilements arise as a result of the contact between mind and body and how they multiply. If one wishes to understand the essence of Dhamma, the essence of truth, one will have to journey within the body. Otherwise, one will give importance only to superficial matters for the whole life.

A great saint of India, Narsi Mehta said-

"Ṣarīra sodhe binā, o sāra nahin sāpḍe."

-‘Without searching within the body, one cannot find the essence of truth’.

The essence of truth will become clear only when the entire truth about this body and mind is experienced. Once one understands this, the way to liberation is opened. For this, one has to explore the truth within the body. This is what the saints did.

Another saint of India said –

"Tīna hātha eka aḍadhāyī, aisā ambara cīhno mere bhai! Aisā ambar khojo mere bhai!"

- Explore the sky, the space within the body, gain full knowledge about it.

If one practices this technique in its pristine purity, one will achieve this aim. Those who preserved this technique in its pristine purity for the past 2500 years have found that anyone practicing it benefited from it and developed purity of mind. Therefore, this technique should not be changed in any way-one should not try to add or remove anything from this technique. Then, it will continue to produce the same beneficial results. One must observe pure breath, natural breath, as it comes in, as it goes out. Just continue to observe and everything regarding the body and the mind will become clear at the experiential level.

What does the ordinary meditator actually know about his body? He may have read some book on anatomy and have the delusion that he knows very well what the body is, inside and outside. But he has not experienced these truths. He has experiential knowledge about the external organs such as the limbs and eyes that work according to his desires. If he wants to raise his hand, he can raise it; if he wants his eyes to open, he can open them; if he wants them to close, he can close them. He can make them work as he wants. But there are many large organs inside the body like the heart, the lungs, the liver, and other important organs, which work independently, naturally, according to nature's law; they do not wait for instructions. One cannot make them work as one wants. One cannot make them work more quickly or more slowly or stop them from working. They work on their own. One knows nothing about them at the experiential level. One may have intellectual knowledge, but unless it is accompanied by experiential knowledge, it is incomplete. It only serves to satisfy one's curiosity. Intellectual knowledge is important but it should be accompanied by experiential knowledge about one's body and mind.

It is with the help of the breath that one starts the journey within. For three days one keeps all attention at this door of the body, that is, the nostrils. The breath is coming in, the breath is going out. One develops the ability to continuously observe incoming breath and outgoing breath at this spot. Remaining aware in this way, one is increasing one's ability to perceive the truths within the body. One thing about respiration becomes clear: it is not merely a physical process; it is intimately connected to the mind and even more to the mental defilements. This becomes clear by direct experience but only if one observes natural respiration. If one adds a word, a form or an imagination, or starts some breathing exercise, one becomes entangled in it and loses awareness of the breath.

There are two fields in the body: the known field-the field of the external organs and the unknown field-a bigger field about which we have no experiential knowledge. We have to move from the known field to the unknown field and understand it. To achieve this, we take the help of respiration. Respiration is a function of the body that works according to our desire but also works automatically. One can breathe faster or slower or even stop breathing for some time. So we can control our respiration if we wish but otherwise, it continues to work automatically. One automatically breathes in and out. Since the breath functions in both ways-according to our instructions as well as automatically-it can be used to understand the unknown field of the body, which works automatically and about which we wish to gain more knowledge.

An example:

A person living on the bank of the river knew everything about it through his experience since he lived there. He had never gone to the other bank, so he did not know anything about it. A person who has crossed the river to the other bank described the other bank to him-"Oh, the other bank is so wonderful! It is so beautiful! It is so charming!" So the person living on this bank felt-"I should also see the other bank. I should also enjoy the beauty of the other side." So what did he do? He stood on this side of the river, folded his hands, and with moist eyes and in a distressed voice, he made a fervent prayer-"O other bank of the river, please come over here. I want to see you, I want to enjoy your beauty." Even if he cries all his life, the other side is not going to come to him. If he wants to enjoy the beauty of the other side, he will have to cross the river and go to the other side. Only then can he see the other bank. How can he reach the other bank? He can reach there with the help of a bridge that joins this bank of the river to the other bank.

The two banks of the river are like the two fields in the body: the known field, where the organs work voluntarily, according to one's wishes, and the unknown field, where the organs work on their own. But the breath comes in and goes out according to one's wishes as well as automatically. So respiration is connected to the known field as well as to the unknown field of the body. Therefore, it can serve as a bridge between the known and unknown fields. By the observation of pure respiration, one can reach the unknown field where things work on their own.

The object of meditation should be natural respiration only. When the breath is coming in, one observes that it is coming in; when the breath is going out, one observes that it is going out. As one continues to observe natural respiration, the subtlest truths of the body and the mind will be revealed until one reaches the ultimate truth, a state beyond both the body and mind.

“Saans dekhte dekhte, satya prakaṭatā jāya, Satya dekhte dekhte, parama satya dikh jāya."

-‘Observing respiration, truth manifests itself, Observing truth, the supreme truth manifests itself’.

If one observes natural respiration, one will understand everything about the body. As one progresses on this path, the body that appears so gross will gradually start to disintegrate until one reaches the stage where one can feel the entire body to be subatomic particles arising and passing away, arising and passing away in the form of wavelets. One has to reach that stage. One may have read books that say that the entire material world is made up of sub-atomic particles and each sub-atomic particle is nothing but wavelets. What does one gain by that? But if one experiences this truth, one understands the close interrelationship of the breath with the mind and the mental defilements. One also discovers the interrelationship of the body with the mind and mental defilements. Gradually, one will reach a stage where one can observe how the defilements arise and multiply in the mind and what part the body plays in it, what part the mind plays in it. When all these truths are realised by direct experience, one is able to eradicate these defilements. Otherwise, one continues to remain deluded.

If a defilement such as anger arises, one always tries to find the external cause-"This person has abused me. That is why anger has arisen and I have become agitated." But the cause of your anger, the cause of your misery, is not outside. When you begin to look within, you will clearly understand that there is a link between the external event and the misery that has arisen within. When that link is observed, one gains understanding about it and learns to remove the cause of one's misery.

But this will happen only when one understands the truth by direct experience. Intellectual understanding of the truth may be of some benefit. But the intellect is a very small portion of the mind. The remaining vast portion of the mind which is full of defilements remains unseen, remains unknown. One remains satisfied by purifying only the surface part of the mind but this is not sufficient to purify the mind.

With the help of the breath, one clearly understands the interaction between the body and the mind: how they affect each other and the breath resulting in the generation and multiplication of defilements. By observing it, one will learn to come out of defilements.

Only by eradicating defilements can one practice pure Dhamma and apply it in life. As one continues to purify the mind, one's life becomes full of Dhamma, full of happiness, full of harmony. Indeed, one who practices Dhamma gains real happiness, real welfare, real peace, real liberation.