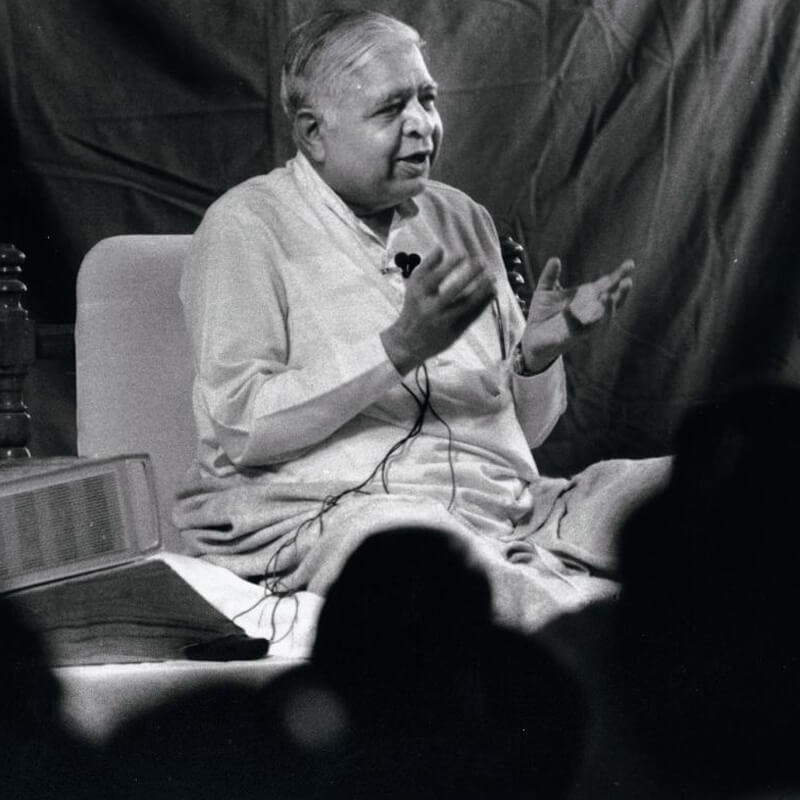

(Following is an extract from the talk given by Goenkaji at Yangon University in Myanmar on September 6, 1991, the first of a series of three. It has been edited and condensed for publication.)

This is the beauty of the Buddha’s teaching: It is so complete that nothing has to be added to it. If you just practice sīla, samādhi and paññā, that is enough. And it is so pure that nothing has to be taken out. Nobody can find anything wrong in sīla. Nobody can find anything wrong in samādhi. Nobody can find anything wrong in paññā. People are sure to accept it. And they are accepting it.

If we make a sect out of the Buddha’s teaching, a blind faith or a cult or philosophy, then difficulty arises. Every sect will have its own philosophy, cult, belief, dogma, rites, rituals, ceremonies, and they all differ.

But when you take the essence of the Buddha’s teaching—sīla, samādhi, paññā—everyone is bound to accept it because it is so scientific.

A Buddha teaches Dhamma. A Buddha does not establish a particular religion. A Buddha is not interested in establishing a sect.

On one occasion, when the Buddha was explaining Dhamma to some people, he said: “I am not interested to make you my disciples. I am not interested to snatch you away from your old gurus. Your aim is to become liberated from misery. I am not interested to take you away from that aim. Everyone wants to come out of misery. Nobody wants to live a miserable life. I am here to help you fulfill your aim, to come out of misery. I have a technique for doing that. Give it a trial.”

This was Buddha’s way of teaching. He was so detached.

If so many people in the world start calling themselves Buddhists, do you think Buddha would be very happy about that? Not at all. If people start practicing sīla, samādhi, paññā, then Buddha’s teaching has started giving fruit. Suppose one calls oneself a Buddhist but does not practice sīla, samādhi, paññā. What benefit will that person get from the teaching of the Buddha? Suppose one does not call oneself a Buddhist but practices sīla, samādhi, paññā; that person will get the benefit, will come out of misery.

The teaching must be practiced, and practiced at the experiential level. Merely playing devotional or intellectual games in the name of Dhamma is not sufficient. It is the experiential part of Dhamma that gives results.

Other spiritual teachers kept saying, “Live a moral life. Develop control of the mind. Purify your mind. Remain detached. Remain free from craving, free from aversion.” But no one else could say, “This is how to become free of craving and aversion. This is how to purify your mind at the deepest level.” The biggest contribution of Buddha was that he explained how.

The Buddha’s teaching seems so simple, but to actually practice Dhamma is difficult. One has to work hard. Listening to discourses or reading scriptures or discussing what you hear is good. But if you keep on just discussing and debating without practicing, it doesn’t work. You have to start taking steps on the path of Dhamma. Otherwise, you don’t get the fruits of Dhamma.

A Buddha teaches Dhamma, the universal law of nature, which is applicable to one and all. And he teaches in very simple language. We make it complicated. Instead of practicing it, we make it into a philosophy and we start fighting: “Your belief is wrong. My belief is right.” What will we gain by that? Even if my belief is in fact right but I don’t practice it, what is the use of this belief?

I am grateful and proud to have been born in the Dhamma land of Myanmar. Eighty percent or more of the people here do not believe that there is a soul inside. Eighty percent or more do not believe in a God Almighty who created the world. And for more than two decades now, I have lived in India and traveled to other countries. Eighty percent or more of the people there believe that there is a soul inside, that there is a God Almighty who created the entire universe. What difference does it make?

Before I came into contact with my teacher, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, before I came into contact with the practical Dhamma given by the Buddha, I used to play this game myself, the game of philosophical arguments and debates: “There is a soul. No, there is no soul.” You have a thousand arguments that there is no soul and your opponents have a thousand and one arguments that there is in fact a soul. You have a thousand arguments that there is no Creator God and they have a thousand and one arguments that there is. Where will you reach by these debates and arguments? They don’t take you anywhere.

When you practice Dhamma, you can experience for yourself that a person is nothing but the interaction of mind and matter. At the apparent level, this phenomenon looks so solid. But when you observe it as the Buddha taught, as the Dhamma instructs, as the law of nature requires, you will find that the solidity dissolves. It becomes divided, dissected, disintegrated, and you see that it is mere vibration. Sabbo pajjalito loko, sabbo loko pakampito—The entire universe is nothing but combustion and vibration.

This was a wonderful discovery of the Buddha, which no other teacher before him could achieve. Although things look solid, that is only apparent truth. The actual truth, the deeper truth, is that everything is mere vibration, vibration, vibration.

This has to be experienced. Suppose you do not experience it and instead make it a philosophy: “Look, there is no attā, there is only vibration.” How will this help you? But when you experience it yourself, you will find that your ego is gradually dissolving. You come out of your ego. You are a liberated person. And that is anattā—no ego.

Suppose you keep on saying “There is no soul” but you are full of ego. If that is the case, Buddha’s teaching will not help you. You have not learned anything from the Buddha. But when your ego dissolves, then you understand by experience, “Look, there is no soul. Only mind and matter, and the interaction of the two. Mere vibrations, mere vibrations.”

It is not an intellectual game. It is not an emotional or devotional game. It is not a blind belief, it is not a dogma, cult or philosophy. It is the truth, and it can be realized by one and all. It makes no difference whether you are a Christian or a Muslim or a Hindu or a Jain. It makes no difference whether you are a Burmese or an Indian or an American or a Russian or a Chinese. The law of nature is applicable to everyone.

Some people accepted what the Buddha taught and some rejected his teaching. So what? He simply discovered something for the good of others and distributed it to people. If somebody rejected his teaching, the Buddha did not lose anything as a result. He was there to explain the truth to people.

Just as Newton explained gravity, and Einstein explained relativity, the Buddha explainedpaṭiccasamuppāda, Dependent Origination. This is the law of nature. If, out of ignorance, one does not know that every contact with a sense object gives rise to a sensation within the body (phassa-paccayā vedanā), if one does not have the ability to feel the sensation, then how is it possible to understand that the sensation gives rise to craving (vedanā-paccayā taṇhā)?

With compassion the Buddha explained: “Look, this is why you are miserable, because vedanā-paccayā taṇhā—sensation gives rise to craving in you. But I will show you a way to come out of the misery. Sensation will still be there, but no more craving, no more taṇhā. Every time you experience a sensation, wisdom must arise: ‘Oh, anicca, anicca, anicca.’ Whatever the sensation, it is impermanent.” By experience, you come to realize this.

If this becomes a philosophy or theory for you, you don’t gain anything. You must experience it: “Look, a vedanā has arisen. And sooner or later, it passes away.” However unpleasant a sensation may be, however pleasant it may be, it is bound to pass away. It does not stay. It arises and passes away—udaya-vaya, udaya-vaya.

This was the unique contribution of Buddha. He told people, “Understand this law. The vedanā is there all the time. It arises and passes away repeatedly. And because you’re ignorant of it, you keep on reacting. If it is pleasant, you react with craving. If it is unpleasant, you react with aversion. This is what you are doing all your life. And you are creating misery after misery for yourself. You keep on multiplying your misery. But look, there is a way to come out of misery, a way to reach the stage where taṇhā-nirodhā dukkha-nirodho—craving ceases and therefore misery ceases. No more dukkhanow. There is a way, there is a practice, there is a technique to do this.”

If the Buddha had simply given sermons, he would have been just another intellectual or philosopher, one of many in India. No, no. The Buddha was a practical person. He became enlightened because he practiced this technique.

I was born into a staunch, conservative Hindu family, and all our scriptures told us the same thing: “Come out of craving and aversion.” But they did not explain how to do it. When I went to my Dhamma father, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, I received a new life. The shell of ignorance was broken and I began to experience the truth of anicca inside.

Through the practice of Vipassana, Sayagyi taught me to experience the reality at the deepest level: “This is where craving and aversion arise—at the depth of your mind, in the interaction of mind and matter within the framework of the body.” When he made me realize that, I felt so grateful to him.

The Buddha’s teaching fascinated me because of the practice. If it was only an intellectual exercise, I doubt that I would have followed this path. I would have said, “Very good. Our Hindu scriptures teach the same thing. Wonderful.” I would not have walked on the path.

But I was given a technique: “Look, this is how you can come out of craving and aversion.” And it worked. I had been such an angry person, full of ego, but when I started applying the technique I found that these mental impurities started to dissolve. And not merely at the surface but at the deepest level of the mind.

I feel very fortunate that I was born in this wonderful land of Dhamma. In all my travels around the world, I have found nowhere else where the pure technique of Vipassana was maintained. I am very fortunate to have been born in a country where it was maintained in its pristine purity.

And I feel very fortunate that I encountered a saintly person who showed me the technique so compassionately and freely, without expecting anything in return. He never sought to convert me, to make me a Buddhist. Far from it. Instead he said, “You become a follower of sīla, samādhi, paññā, and I will be quite happy.” I feel so fortunate to have come in contact with him.

And, my brothers and sisters who are here, you too are very fortunate to have been born in this country, enabling you to come in contact with the Dhamma.

Now the most important thing is to practice the teaching. Simply accepting Dhamma at the devotional or intellectual level will not give you anything. It is the practical, experiential Dhamma that gives results.

May all of you taste pure Dhamma at the experiential level. May all of you come out of your misery. May all of you enjoy real peace, real harmony, real happiness.

(Courtesy: International Vipassana Newsletter, Vol. 42 (2015), No. 2 , June 4, 2015)