Bhāradvāja was of the view, that one is a brahman if one is born to parents whose lineage back to seven generations is pure. By virtue of this, one becomes a brahman. Young Vāśisṭa, on the other hand, said that if one is virtuous and moral, he is a brahman. When the two could not come to a conclusion, they approached the Buddha, introduced themselves to him and requested him to explain whether one is a brahman by birth or by action.

The Blessed One explained to them in detail giving reasons for the differences among all beings. Their birth is their distinctive mark. All species of living beings are different from one another because of their birth. Various kinds of trees, plants and grass are also different from one another. Insects, flies and ants have different distinctive marks. Various kinds of snakes, aquatic creatures, fish and birds have different distinctive marks. Human beings, on the other hand, do not have such distinctive marks. Every limb of the body of a creature or being is different from the limbs of other creatures. But as far as man is concerned all parts of the body of all men are the same.

The differences in men are only external. One who earns his livelihood by keeping cattle is a peasant. One who carries goods is a laborer. Those who eke out their living by any handiwork, craft or art, are called potters, iron-smiths, carpenters, etc., depending on their profession. The one who trades for his livelihood is called a trader. One who steals from others to make a living is called a thief. One who lives by using arms and armaments is called a soldier. One who possesses land and villages is called the King. None amongst them is a brahman.

Then, the Lord said, that no human being becomes a brahman just by virtue of being born to a particular mother. He explained further the qualities, by virtue of which a person becomes a brahman.

He, who does not hoard, who is free of attachment and greed, is fearless having broken all fetters that bind him to the wheel of birth and death, who has driven out anger and craving from the mind, who has broken himself free from all wrong views (62 kinds of wrong views were prevalent in those days), who is fully enlightened, him I call a brahman.

I call him a brahman, one who bears insults and pains without reaction, without being angry i.e. without polluting his mind, whose strength is forgiveness, who is free from anger, who is virtuous, moral, learned, and abstemious, and for whom this is the last birth. I call him a brahman who does not cling to sensual pleasures like the water drops on a lotus leaf, or in whom jealousy, pride, craving, and aversion do not stick, like a mustard seed on the tip of a needle, who has ended sorrow in this life and has thrown off all his burden, who is of deep wisdom, learned, who knows what is the path and what is not the path, is honest, who is neither attached to householders nor to those who have left home for the homeless life, who neither kills any being, nor instigates others to kill, who is peaceful amongst adversaries, without any stick amongst those armed with sticks, a non-hoarder amongst hoarders, who is respectful, and whose words are sweet and true, words that never hurt others, a person so qualified I call a brahman.

Thus, the Blessed One described further the virtues of a brahman. One who doesn’t take anything in this world which is not given to him, who is free from craving for this life or the life beyond, who has realized the ultimate truth, who shows the path to liberation, who is free from sorrow, who is untainted and pure, who is attached neither to sin nor to virtue, whose cravings for all his births have been rooted out, who has forsaken the ignorance that causes the cycle of birth and death, who has become an ascetic giving up all enjoyments, who is unfettered by all worldly and heavenly bonds, and who having discarded the likes and dislikes has become calm and cool and free from defilements, such a universally victorious person do I call a brahman. One who knows the passing away and arising of all beings very well, who is desire less, free from rebirth, who is endowed with wisdom, him I call a brahman. Neither a Deva, nor a Gandharva, nor a man knows his course, who is free from taints, is an arahant, who has nothing before, after or in the middle, who is without any property, who knows his previous births, sees heaven and hell, who is not going to be reborn, all that he had to do has been done, and who is an enlightened sage, him I call a brahman."

One is not a brahman or a non-brahman by birth. One is a brahman or a non-brahman by actions. One's occupation makes one a peasant, and another an artisan. Occupation makes one a trader and another a laborer. Actions make one a thief and another a soldier. Action makes one a beggar and it is action alone which makes one a king. In this way, the wise man who knows the results of kamma, knows this life very well. The world moves on because of kamma (actions), people also move in the cycle of birth and death because of kamma. All beings are tied to their actions like the moving wheels of a chariot tied to the axle. Meditation, living a holy life, abstinence from sensual pleasures and controlling the mind – these make one a brahman. Those who have these qualities are the best brahmans.

Though those two were young, even the elders of the Brahman community frequently discussed the topic.

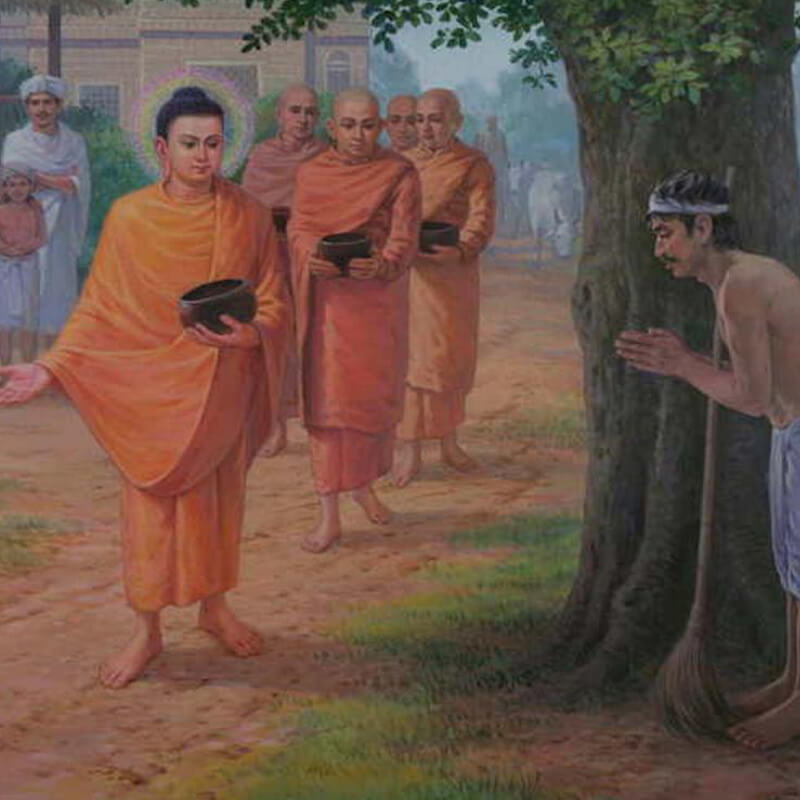

Here is an incident from the life of the Buddha. Once when the Buddha was living in Anāthapindika's Jetavana monastery, 500 Brahmans from different places gathered in Srāvastī;. Their topic of discussion was that Gotama does not make a distinction between high and low castes. He teaches Dhamma to people of the lowest caste and makes them respected and revered. We are not able to debate with him on this point."

One amongst those Brahmans was Ᾱśvalāyana. Though young, he was an expert of the Vedic literature. It is believed that he was the same Ᾱśvalāyana , who later became a scholar in the Upaniṣadic era. Hence the group of Brahmans felt that Ᾱśvalāyana was capable of debating with the Buddha on that topic and helped him get ready. Although he repeatedly said that the Buddha speaks the words of Dhamma, and it is difficult to debate with him, but because of the pressure of those brahmans, Ᾱśvalāyana became ready to debate with the Buddha.

When he met the Buddha, he said that the Brahmans claim that they are the highest caste, others are inferior. They are fair, others are dark, only the Brahmans are pure, and others are not. Brahmans are born of Brahmā, are born of his mouth and they are his true heirs.

To this the Buddha replied, "Ᾱśvalāyana, the brahman women also menstruate, become pregnant, give birth to children and suckle them; so how can we accept that they are born of the mouth of Brahmā?"

Aśvalāyana remained silent. He could not refute.

The Blessed One further said, "If any Brahmā has decreed mankind to be high and low, then why are there only two classes of mankind in the neighboring countries and in other bordering states - noble and slave? There, if one is a noble, he can become a slave and a slave can become a noble." Aśvalāyana accepted that in these states and countries, this is how things are.

The Buddha then asked him the special quality of the brahmans on account of which they consider themselves to be the heirs of Brahmā.

Aśvalāyana had no answer to give.

The Buddha further said that if a Kṣatriya is cruel, if he is a thief, is immoral, if he speaks harsh words then he will be born in hell after his death. In the same way, the Vaiśya (traders) and the Sūdra(menial workers) will also meet the same fate i.e. they will go to hell if they are like him. Will a Brahmin not be born in hell if he has these characteristics?

Aśvalāyana had no answer to this.

"Similarly, if a man is of good conduct, he will go to heaven on death, whatever be his caste."

Aśvalāyana remained silent.

The Blessed One said, "Whether one is a brahman or a non-brahman, he can remove his dirt by applying soap on his body and taking a bath in the river. Then why is a brahman special? Similarly, one belonging to any caste can, on coming to me, remove the defilements of his mind and become a Dhammic person. It is not necessary for him to be a brahman. Everyone has the right to be moral and upright. And everyone who becomes moral and upright will get the same results. I call such a meditator a real brahman. Any meditator, regardless of caste, can be rightfully called a brahman if he practices meditation, lives a holy life, controls his sense organs and mind. Such a meditator, I call a superior brahman. One belonging to a so called lower caste can also achieve purity by his wholesome actions and good conduct."

Aśvalāyana again found no suitable reply to give.

The Buddha further asked, "If a Brahman young man marries a young non-Brahman woman, or if any non-Brahman young man marries a young Brahman woman, then what will you call the child of such a couple? Superior or inferior? A brahman or a sūdra?"

Aśvalāyana remained silent.

The Buddha further said that when a horse mates a donkey the offspring is called neither a horse nor a donkey. Rather, it is called a mule. But what will you call the child of a brahman father and a non-brahman mother? Will he be called a high caste brahman or a low caste sūdra? How will you differentiate?

Man is man. There are no differences. Every one, whether one belongs to the brahman caste or to any other caste, has the right to be moral and upright. All who are moral and upright get the same result.

Unfortunately, thousands of years before the Buddha, the country was ridden with high and low castes and untouchability. There were other bad practices. The sight of a Cāndāla was considered unlucky and an ill-omen. Leave alone his touch, one needed to bathe, if even his shadow fell on him. So, a Cāndāla, had to come clapping or ringing bells from a distance thus intimating the group of people of his coming. Many would wash their eyes with perfumed water, if their eyes fell on a Cāndāla. Often, people would beat a Cāndāla, if his shadow fell on them. Cāndāla would keep their eyes lowered when they entered the village.

It seems that even after the Buddha, Cāndāla would carry corpse and guard the cremation ground. They lived in separate villages and there were separate cremation grounds for burning their dead bodies.

Apart from Cāndāla, there were also others, who were considered to be very low. They were Nesadas i.e. those who made cane/ bamboo baskets, Camārs, i.e. those who made objects from the leather of dead animals and Pukkusas, i.e. sweepers and cleaners who would dispose of human excreta.

The members of the Cāndāla clan were considered outcastes. The Buddha described who truly is an outcaste. "The man who is hot tempered, jealous and hostile, is a sinner, holds wrong view, is a fraud, is cruel, is a tormentor, is a thief, is licentious; one who doesn't take care of his old parents, troubles others, deceives brahmans, monks or other beggars; utters words that cause harm; hides his immoral acts; praises himself and derides others; who is angry, is a glutton, who is full of ill-desires; is a miser, is wicked; is neither ashamed nor afraid of wrong doings; who calls himself fully liberated without being so; such a man is an outcaste and despicable. One is neither an outcaste by birth nor a brahman by birth. Actions make one an outcaste and another a brahman. A brahman doing unwholesome actions is a Cāndāla.

The Buddha said, "I do not call one a brahman, because he is born to a brahman mother. I call him a brahman, one who possesses nothing and who takes nothing. Not by matted hair, nor by clan or family (caste) nor by birth does one become a brahman, but one who is truthful and righteous, pure and dhammic is a brahman."

The Buddha always put a premium on one's knowledge and conduct, not on his caste.

Come meditators! Let us also be inspired by the pure teachings of the Blessed One, improve our conduct, perform wholesome actions and become brahmans in the true sense of the term!