(From the forthcoming VRI publication: The Sammāsmbuddha in The Tipitaka,Vol 2.)

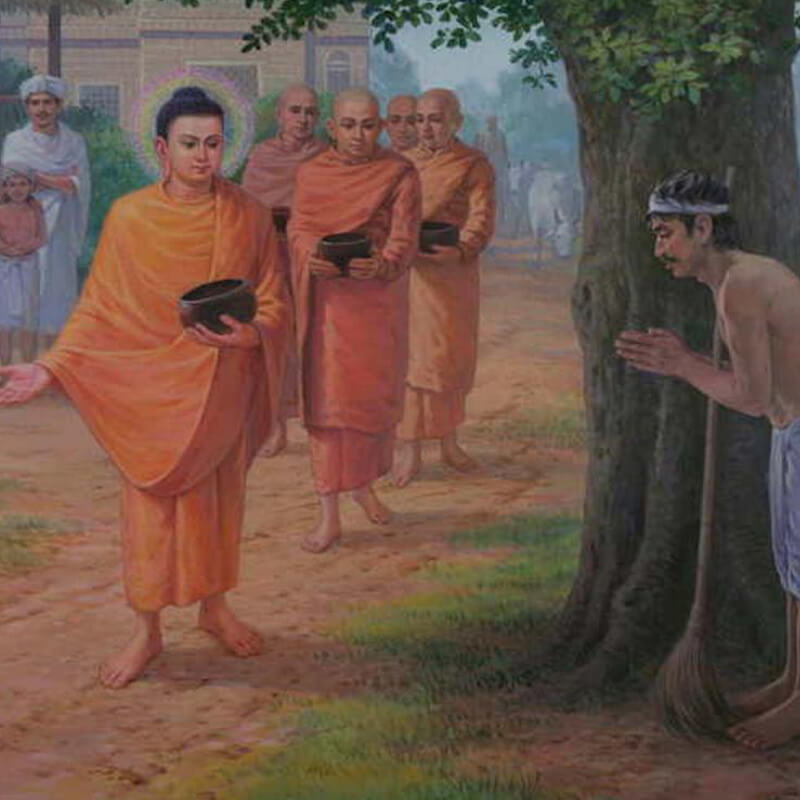

King Prasenjit of Kosala was once on a state visit to the Sākya country. He went in his chariot to relax in a park in outskirts of the city. Reaching the forest, his chariot could proceed no further through dense vegetation, and so he had to walk to continue his journey.

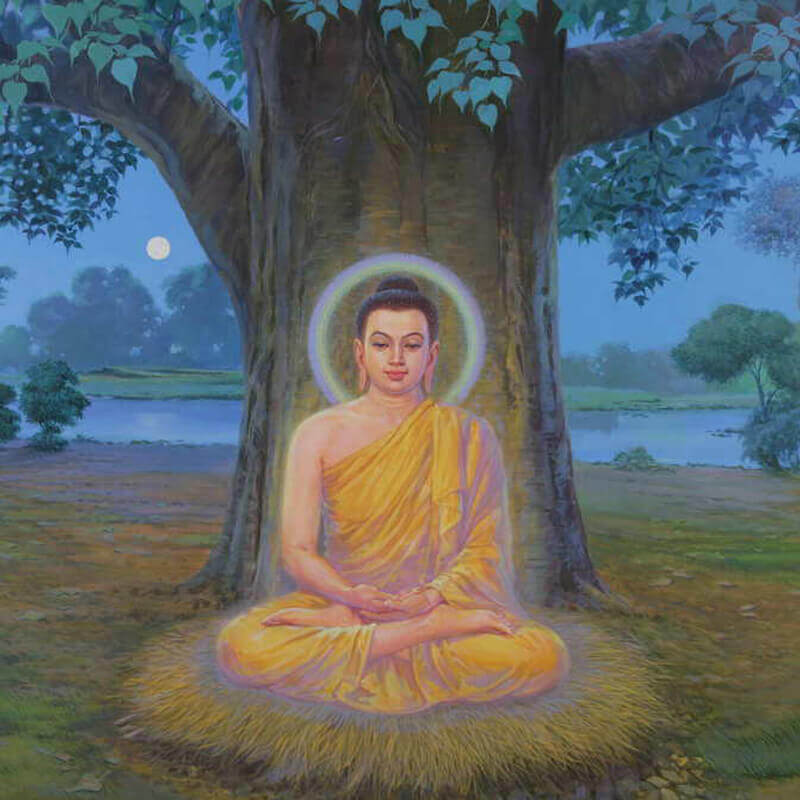

Walking through the forest, King Prasenjit saw tall trees towering amid stillness and silence. He experienced the quietness of the woods undisturbed by voices, a deep solitude far away from noise, and chatter. This was a place conducive for serious meditation. He was reminded of the times when he had often met the Buddha in such places of serenity. He wondered if the Buddha was in the region. On enquiry, he found that the Buddha was indeed teaching in a place nearby at that time. Quiet places of seclusion and solitude became synonymous with the Buddha and those practicing the Buddha’s teaching.

The Enlightened One favored peace, silent meditation and solitude. But it did not mean he avoided his duties and responsibilities as a Vipassana teacher. He maintained his connection with his students, always ready to guide them when needed.

The depth of his universal, practical teaching and the number of his discourses (85,000) during 45 years of selfless Dhamma service far outnumbers the discourses of any other spiritual teacher in the long history of mankind. His entire life as the Buddha was full of compassion. He constantly worked for the benefit, the happiness of many. He was always busy in Dhamma work. True are these words about the Buddha:

‘Asammohadhammo satto loke uppanno bahujanahitāya bahujanasukhāya lokānukampāya atthāya hitāya sukhāya devamanussānan’ti. – Majjhima nikāya 1.50 Bhayabheravasuttam

-‘Out of immeasurable compassion, for the well being of all, for happiness and welfare of gods and men, a being free from delusion, has arisen in the world’.

The Buddha has himself said how he continued to serve beings.

‘Aññatra asitapītakhāyitasāyitā aññatra uccārapassāvakammā, aññatra niddākilamathapaṭivinodanā apariyādinnāyevassa, sāriputta, tathāgatassa dhammadesanā, apariyādinnamyevassa tathāgatassa dhammapadabyañjanam, apariyādinnaṃyevassa tathāgatassa pañhapaṭi-bhānam’..

– M.1.161, Mahāsīhanādasuttam

-‘O Sariputta, barring those times when the Tathāgata partakes of little food once a day, attends to calls of nature or briefly rests his body, he expounds the Dhamma tirelessly and explains the intricacies of it, answers questions on the Dhamma day and night.

Rest and Meditation

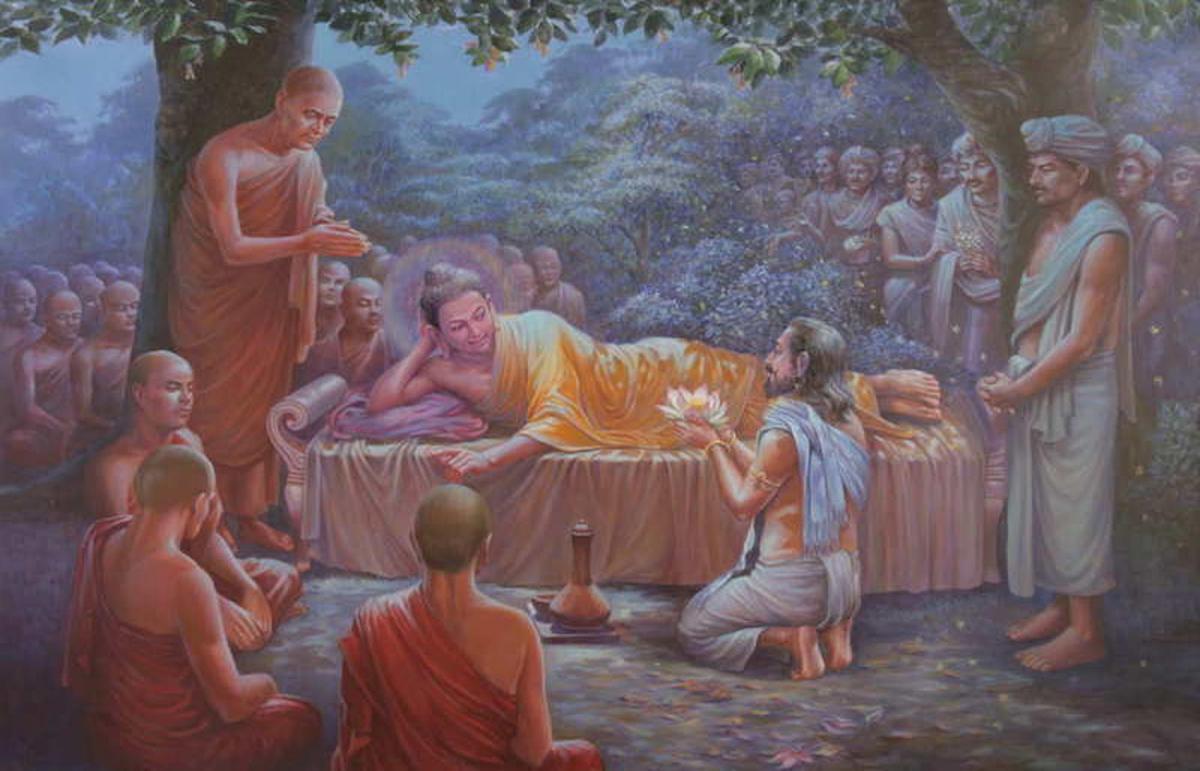

While the ultra-pure mind of a Sammāsambuddha is of tireless strength, his body needed three or four hours of rest in 24 hours. This rest he took in one quarter of the night, but with awareness and equanimity. The Buddha also undertook periodic solitary retreats to practice meditation. The question would arise why one who is free from craving, aversion and ignorance, needed to meditate:

Ajjāpi nūna samano gotamo – avītarāgo, avītadoso, avītamoho

-Is Gotma still not beyond craving, aversion and delusion?

tasmā araññavanapatthāni pantāni senāsanāni paṭisevati!

-Is that why he goes for solitude to the quiet forest?

In order to remove such false understanding, the Buddha explained why he occasionally resorted to meditating in the forest.

Dve kho aham, brāhmana, atthavase sampassamāno araññavanapatthāni pantāni senāsanāni paṭisevāmi – attano ca ditthadhammasukhavihāram sampassamāno, pacchimañca janatam anukampamāno”ti.

– M.1.55, Bhayabheravasuttam

-Buddhas retreat in solitude for two reasons:

For a pleasant abiding here and now, and due to compassion for the future generations.

Meditation in Solitude

The human body has limited capacity, even if it is the body of the Buddha. He too needed rest. Besides this, the Buddha was far-sighted. He knew that some Dhamma teachers of future generations would not practice Vipassana themselves, but would keep asking their students to practice. To ensure that teachers practice what they teach, he established a healthy tradition for the ideal Dhamma teacher – one who ardently continues and deepens one’s Vipassana practice to fully purify the mind.

Although the Buddha himself was completely free from all mental impurities, he never discontinued practicing meditation. The Buddha set a living example of how even a Sammāsambuddha continued to practice Vipassana, even after reaching the final goal.

Students cannot be expected to follow a teacher who does not practice what he teaches. Besides a teacher who is not an arahant (one who has fully purified the mind) can still succumb to latent impurities in the mind. To help future generations of Vipassana teachers avoid such a dangerous mistake, the Buddha compassionately set an example: he went into Vipassana meditation retreats from time to time, to make clear to those in Dhamma service not to neglect the responsibility to eradicate impurities in their own minds.

While there are many benefits and support gained from group meditation, we gain great strength and self-dependence from meditating in seclusion. It is, in fact, incomparable. This is why pagodas in Vipassana centers have individual meditation cells for meditating in solitude. The Enlightened One set the compassionate example by setting aside time, even amid his busy schedule, to meditate alone. He wished to ensure that future generations of sincere Dhamma teachers and Dhamma workers will not succumb to the dangerous delusion, wrongly thinking: “Oh, I am so busy with my Dhamma work today, serving others. I have no time to meditate.”

The Sammāsambuddha, the most compassionate, tireless Dhamma worker of all, found time for daily practice of meditation. There can be no excuse to neglect one’s daily practice of Vipassana.