This is a historic occasion. People who give dana for building a center are actually giving service not only to those who come here for the first course or the second course, and not only to the people who will be coming here in a few years. They are planting a seed in this land, where Dhamma will grow; and for the coming centuries this land will be a lighthouse of Dhamma.” - S. N. Goenka, Dhamma Bhumi, November 1983.

In 1979, for the first time Goenkaji accepted an invitation to teach courses outside India, going to England, France and Canada. In 1980, he was invited to the United States and Australia. His first two courses in Australia were in Sydney and Perth. The courses were organized by small groups of old students using rented facilities: a boy scout camp in Sydney and a youth hostel in Perth. A total of 119 students attended the course in Sydney, and 78 in Perth. A group of parents with small children also stayed just outside the Sydney camp, taking turns caring for their children and meditating or serving on the course.

After these courses, a portion of a large donation was used to purchase a Dhamma house in Sydney, where group sittings and self-courses were held with the support of local meditators. Goenkaji returned to teach larger courses in 1981 and again in 1982, when he also visited New Zealand.

Setting up and dismantling these camps was a major task, and the local meditators recognized the need for a permanent place for meditation courses. They started looking around Sydney for a suitable site. In 1981 they found approximately 38 acres of land at Blackheath, connected to Sydney by rail and road. As one of the search party recalled:

“We jumped in the cars and just took off to have a look. . . . I didn’t see [anything] very attractive coming up here until we hit Blackheath, and then the whole thing changed, the whole atmosphere. We felt really good getting to Blackheath. We just drove straight here.”

Four meditators donated the purchase price for the center.

The Beginnings

Perched on an escarpment in the Blue Mountains, at an altitude of 1,065 meters, the center site has magnificent views of the cliffs and the Kanimbla Valley below and is surrounded by the spectacular Blue Mountains National Park, a World Heritage area. The name of this area comes from the predominant eucalyptus forest: the trees give off a vapor, making the land appear blue from a distance. Covered in flowering heath and eucalyptus, the site is home to many colorful native birds (crimson rosellas, king parrots, kookaburras and black cockatoos) as well as native wildlife (possums, wallabies and kangaroos).

Blue mountains

When Goenkaji revisited Sydney in 1982, he approved the land as suitable for a meditation center and named it “Dhamma Bhumi,” meaning Dhamma soil or Dhamma land. The date of November 1983 was set for the first course at the center, to be conducted by Goenkaji. The race was now on to prepare before the deadline. The land was totally uncleared forest with not even a shed or utilities. Everything had to be built from scratch. One meditator recalls going to a picnic at the site in March and being unable to believe there would be a center there in seven months.

Australia is a large continent with a small population that numbered only 15 million in the early 1980s. This first Australian center was to be built in the way that was common at the time: on uncleared land, on the outskirts of a small town and from scratch. A meditator architect offered his firm’s services to develop the detailed building plans. Creating the center was to be a dramatic mixture of events, as a meditator recalls:

“There were a number of incidents where things happened surprisingly easily, as if Dhamma wanted it to happen, just made it happen; and at other times there were extraordinary difficulties.”

The Blue Mountains City Council granted planning consent to a very informal development application. However, the Council applied much tougher conditions to the building application consent. The center could not be used until completed, and a section of public road, Station Street, leading to the center would have to be sealed at the organization’s expense.

One of the first tasks was building the boundary fence, which defined the meditation compound. This was extraordinarily difficult. Months later, when only the main gate remained to be put in, a sand delivery truck deposited its load right on the site of the gate! Nevertheless the task was finally completed in time for the first course. The Dhamma house in Sydney was sold to provide initial funding for the building materials. Meditators provided almost all of the labor.

In April 1983, three Dhamma workers with building and carpentry skills were flown out from Dhamma Giri in India to form the core building group. They were joined by others, until there was a team of about a dozen workers living in rented property in Blackheath and working every day at the center site. Each day a couple of workers would make a hot lunch and bring it to the site. Others would come up from Sydney to help at weekends.

Old students meditating on the site

To start using the land for meditation as soon as possible, group sittings were held at the site in the open air. Meditators wrapped themselves in blankets and sat on the framework of what was to be the hall.

Earth-moving machines cleared part of the land for the buildings, and created a dam. Work now began in earnest. Initially the going was very tough. The ground was stony and hard, making it very difficult to dig the foundations. With no electricity connection, a generator was used to power everything. The labor was often made harder by frost and ice during a bitter southern winter. As Dhamma workers remember:

“We were working through the winter months. Blackheath is in the mountains. It’s extremely cold. Sometimes those workers . . . were having to break the ice before they could start work. It was very, very tough conditions. Wind was pretty constant throughout the winter, actually . . . clear skies but the wind just came roaring up the valley and it was freezing. I can remember . . . for a full week it didn’t get above two degrees.”

One meditator recalls digging the hundreds of holes for the piers, working “with crowbars through heavy rock and each hole would take half an hour, or sometimes an hour, to dig two or three foot. . . . Eventually the post hole digger arrived. We thought, ‘Salvation!’”

Construction work

Unusual difficulties were experienced with most service connections. Because mains sewage had not been extended to the land, a decision was made instead to pump back to the main sewage line, about 400 meters down the road. The application to do this was delayed and then apparently lost by the local authority. Finally a meeting with the water board’s publicity officer accelerated processing of the final application. Another problem involved the application to lay the sewage connection pipe under Station Street, which was then an unformed, dirt road. This application was refused even though the center had already been asked by Council to form and seal the street at its own expense. Finally, after a meeting with the Council’s chief officer, the problem was resolved and the application was approved.

The site had no three-phase electricity to power the sewage pump. This changed when a senior electricity officer visited the site four weeks before the course and found out that all the workers were volunteers. He was so impressed that he gave orders to extend the three-phase line immediately. The mains sewage connection was completed and the pump tested only the day before Goenkaji arrived to conduct the first course. More meditators converged on the site in the last week or two, working longer and longer days to help finish the buildings and gather together everything that would be needed for the first course.

When the center was finished. it comprised two timber-framed rectangular buildings, set in an open L shape following the contours of the land. One was a dormitory block and the other a meditation hall with accommodation for the teacher at one end. Between the two was an ablution block.

A student remembers the first dining room:

“We built a timber frame and put up this quite large army tent at the western end of the dormitory and that became the dining tent. Meals were cooked and piled into the back of someone’s station wagon and that’s how the cooking happened in the courses.”

The weather turned on a special show, with a sprinkling of snow soon after the first course began. Food was cooked offsite at a local club and delivered by station wagon to the dining tent. The first course was from November 11 to 22, 1983, and a second course was held immediately afterwards, from November 23 to December 3.

Dhamma Bhumi dining hall

Dhamma Bhumi in winter

Being part of the team that built this first center for Australia was a deeply formative experience for many meditators, and greatly strengthened them in Dhamma. As one student said:

“It turned my life around, serving for that period of time. I had an interview with Goenka during that first course and I said, ‘I’ve been working here at the building site,’ and he threw his head back, laughed and chuckled and said, ‘Oh, that’s wonderful, you’ve gained wonderful merits. This will stand you in good stead for years to come.’ And it’s true. I see that it did because I firmly established the two-hour-a-day habit at the time and I’ve been able to maintain it ever since, so it has stood me in tremendously good stead.”

Goenkaji gave all the instructions and discourses in person at this time. However, he had begun to appoint assistant teachers in Australia and other countries to help with the work of spreading the technique of Vipassana meditation, using recordings of his meditation instructions and the daily discourses in English. He came again to Australia in 1984 to conduct courses at Dhamma Bhumi, and inspired, advised and supported the growing community of meditators.

Years of Growth

When Goenkaji visited again in 1986, a new double dining-hall and commercial-sized kitchen were ready for use. Underneath were several small rooms, two dormitories and bathroom facilities. This doubled the capacity of the original accommodation block to over 80 students in total. During the peak Australian summer holiday months the courses were, and are, regularly fully booked, with some students staying in tents. More and more people wanted to learn the meditation technique, especially to experience the teaching first-hand from Goenkaji, and a pattern of growth at the center emerged. Every two years or so, for the first decade at Dhamma Bhumi, major new buildings were constructed.

The first rings of the pagoda, 36 cells in all, were completed for Goenkaji’s visit in October 1990. The work was undertaken at a speedy pace: in mid-September the walls of the inner eight cells were barely completed. Based on the Burmese design of Sayagyi’s center in Rangoon, it was a circular brick construction around an octagonal core, similar to the replica that had been built in Dhamma Giri. On this occasion Goenkaji gave the first Satipatthana course at Dhamma Bhumi. The course was professionally recorded and the discourses filmed. These recordings and videos are now used on English-language courses around the world.

Goenkaji received an invitation to visit Myanmar soon after this course. He has described Myanmar as the land of his birth, both as an infant and in Dhamma. He had applied unsuccessfully for a visa for Myanmar several times over the years since he left in 1969. While at Dhamma Bhumi he applied again, through the embassy in Canberra, Australia’s capital. At the close of the Satipatthana course he received the news that he had finally been granted permission to visit Myanmar. When the meditator courier delivered the documents, Goenkaji beamed and said, “Twenty years of exile have ended.” Soon after this he visited Yangon and met with monks at several monasteries, as well as giving a series of public talks to huge crowds.

On his last day before he left Dhamma Bhumi to fly out to Myanmar, Goenkaji gave an open talk on the lawn below the hall for meditators, their relatives and friends, and other visitors from Sydney and the Blue Mountains. This beautiful talk, followed by a lively question-and-answer session, was also recorded.

Public talk

Vipassana meditation in Australia took another big step forward in 1992, when the first 30-day course was held at Dhamma Bhumi. Twelve new single rooms with attached bathrooms were clustered in small cottages to provide privacy for the 13 students who participated. Another new building was erected, with four rooms on the sides of a small, central meditation hall used for the long course students. This meant that parallel 10-day courses could continue in the rest of the center.

The small long-course hall rapidly became inadequate and in 1997 a teacher’s residence was built, with a central hall for up to 50 people. By now the center was offering bilingual courses for Hindi, Cambodian and Burmese students, and this new alternative hall was used for second-language discourses. It also made it possible to run long and special courses at the same time as 10-day courses.

New teacher's residence

In 1999, Ram Singh and Jagdish Kumari, senior teachers from India, came to Dhamma Bhumi to conduct a 30-day course . They also conducted a four-day workshop for assistant teachers and senior Dhamma workers. Thirty-four assistant teachers, 31 trustees and more than 35 Dhamma workers from all around Australia participated. By that time, almost every other state in Australia had acquired either a center or a Dhamma house. There were operational centers in Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia, as well as New Zealand. Not only had the center atDhamma Bhumi grown, but also the Dhamma had spread.

A New Meditation Hall

In Australia 2000 marked a significant development at Dhamma Bhumi, with the building of a new meditation hall, providing seating for up to 250 students in comfortable conditions. The existing hall was bursting at its seams on the larger summer courses, attended by over 100 students, and it was always difficult to heat or cool, and to ventilate.

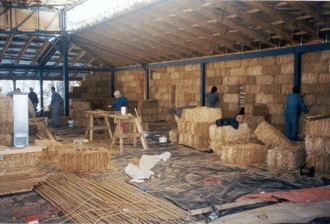

New Dhamma hall construction

After much planning and consultation with an environmental architect, the proposed original design of the hall was considerably simplified into something inexpensive, efficient, and environmentally sound. It was constructed around a pre-made steel frame, with walls of straw bales, and spanned by trusses and large beams. Over the beams a steel roof was raised, with a raised area rising in a pyramidal shape to a central high point. Once the concrete floor slab was poured, the straw bales were assembled inside, protected from the weather, and the walls gradually rose from within.

When the straw-bale walls were completed, they were coated with a plaster skin which proved to be a complicated process. It was a case of trial and error mixing the clay and water. According to a meditator, one unsuccessful mix ”after it dried looked like the skin of an alligator.”

Straw Bale construction

There were 80 tons of dry sand and clay to mix, doubling in volume once water was added. This was hand-mixed and the whole building was hand-coated.

Lantern windows formed part of the roof structure on three sides of the building, creating a uniform light over the floor area. One student described it as ”like sitting in a forest of tall trees, with filtered light coming through them.”

A series of pipes conducting solar-heated water were embedded in the concrete slab, to heat the building. A meditator describes how it feels:

“It works so well for us because the surface you’re sitting on or standing on is warm. You can sit there, on your cushion, with your shawl on, and all that heat is coming up and through your cushion, and the place around you can be quite cool, but your body is warm. It is very good for a meditation hall and I can’t begin to think of anything that would work as well.”

Ambient noise was a big problem with the nearby highway and the railway, and so the ceiling was lined with a densely packed straw board. As a builder recalls:

“In most buildings the main surface area is the ceiling, not the walls, so if you don’t adequately insulate and soundproof the ceiling all of the benefit of the straw bales is pretty well negated. To insulate the narrow band of windows that go round three sides, we put in double rows of windows. This worked well for soundproofing.”

High-quality finishing with painting—a soft golden color for the internal walls and the rendered outside walls with pre-cast dark blue internal posts—gives the impression of a calm, spacious welcoming place.

New Dhamma Hall

The leader of the building team was struck by the efforts of “the dozens upon dozens of people who came to serve that made the hall possible. Working with them was for me priceless, absolutely inspiring. I would say easily 80 percent of the labor was donated and because of that we built a building that works very well. And I think we did it at a very reasonable cost because of all the help we got.”

The hall, started in February, was just ready for the last and largest course of the year, starting on December 26, 2000. A builder said:

“I remember that the day before the course they [students] were helping clean the final bits and pieces of clay [off] the floor to get ready for the course. This seems to be part of the tradition—the building tradition—where even though the building was a long way from finished, the structure was there, everything was in place so that we were able to hold the course.”

At the front of the building, there are two large glassed-in anterooms where students leave their shoes. Between the anterooms is a smaller hall used for second-language discourses. The area on the eastern side of the hall was landscaped in 2004. The western and southern sides will be landscaped after the pagoda extensions are finished.

New Dhamma hall-exterior view

Goenkaji has said that if the gardens are beautiful at a center, half the work is done. From the early years at Dhamma Bhumi students have planted many flowering shrubs, trees and bushes at the entrance and around the ponds and buildings. Many of the trees are now mature, contributing their own color and beauty to the center.

Over time, there has been a gradual but steady increase in the quality of the center’s accommodation. In the early years, to cope with the numbers and limited accommodation, bunk beds were used. They have gradually been removed. Instead, more private or single rooms have been built, currently including 36 single rooms with attached bathrooms. This is in line with a change in the profile of the meditators who come here. As Vipassana has become more accepted in society, as more and more people hear of Vipassana, and as taking a course is regarded as something normal and mainstream, the meditators who come often tend to be older, professional people, such as nurses, teachers, doctors, lawyers, and business people. Of course, because Sydney is a major tourist venue, young backpackers, travelers and holidaymakers also make up a significant part of the center’s students.

The Pagoda

An important part of Dhamma Bhumi is its pagoda and meditation cells, situated between the Dhamma hall and the Teachers’ residence. The original pagoda structure, built in 1990, consisted of two concentric rings at ground level; an inner ring of 8 cells and an outer ring of 24 cells. It was always intended to be the core of a larger structure that would include many more cells at the appropriate time, and has remained a simple, unadorned brick structure up to now. The existing cells served their purpose well, but for several years have proved too few to serve the students who come—or would like to come—to Dhamma Bhumi. There have been waiting lists for the longer courses, with applicants unable to gain admission. On the 10-day courses there are also not enough cells, and old students have to share them, using them at different times of day.

As a first step, a further upper eight cells of the pagoda were completed in 2007, in time for the first 45-day course at Dhamma Bhumi. Plans were drafted and submitted, and—after a protracted period—approved by Council to complete the pagoda. There will be another outer ring of cells on the ground floor and an upper storey with 36 cells, providing over 90 cells when completed.

New Pagoda

The finished pagoda will be surmounted by a golden-colored dome in the Burmese tradition, and will be a reminder of the lineage of past teachers and the debt owed by this tradition to Myanmar. Its grace and beauty will also make a fitting focal point for the center. Construction is expected to begin in 2009.

With the availability of the pagoda cells, long courses have become a regular feature of the Dhamma Bhumi calendar. By holding 30- and 45-day courses, Dhamma Bhumi is actually serving the entire region of Australia and New Zealand. In the long run, however, Goenkaji has advised that each separate region should have its own dedicated long course center. This provides considerable economies of scale since separate, more private facilities are needed for long course students, enabling them to meditate at deeper levels without fear of disturbance.

In 2006 Goenkaji gave his blessings for such a regional long course center to be developed next to Dhamma Bhumi. There will be many advantages from the proximity to Dhamma Bhumi. However, such a long course centre requires additional land. Three blocks of land next to Dhamma Bhumi have been identified. The first and closest block was acquired last year; the third and furthest away was already held by a group of meditators in readiness for acquisition by the center. The second lies between them and is yet to be acquired. Preliminary plans for the long course center, based on the acquisition of this land, have been drafted. It is planned to cater for up to 80 students, and to be used for Satipatthana, special 10-day and executive courses.

Dhamma Bhumi has been created and sustained by the efforts of a very large number of students. Members of the local community and others from all over Australia, as well as visitors from outside the country, continue to serve Dhamma here.

”Those people who give service here, in starting the Dhamma wheel rotating in this country, develop wonderful parami. This is no ordinary thing. Providing a facility where so many people are getting benefit, now and in the future, is a great Dhamma work.”

—S.N. Goenka,Dhamma Bhumi, November 1983

(Courtesy: International Vipassana Newsletter, September 2008 issue)